You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Africa’ category.

Silvia Federici is one of the most important political theorists alive today. Her landmark book Caliban and the Witch demonstrated the inextricable link between anti-capitalism and radical feminist politics by digging deep into the actual history of capital’s centuries-long attack on women and the body.

In this essay, originally written in 2008, she follows up on that revelation by laying out her feminist anti-capitalist vision, and how it extends beyond traditional Marxism. This piece is comprehensive – long but far-reaching. At times seeing the truth requires seeing in the dark – acknowledging the true horrors of the world as it currently is manifest.

This essay was updated and published in Silvia’s new anthology Revolution at Point Zero, and I have made a few small additional edits. Enjoy! [alex]

The Reproduction of Labor Power in the Global Economy and the Unfinished Feminist Revolution (2011 edition)

“Women’s work and women’s labor are buried deeply in the heart of the capitalist social and economic structure.” – David Staples, No Place Like Home (2006)

“Women’s work and women’s labor are buried deeply in the heart of the capitalist social and economic structure.” – David Staples, No Place Like Home (2006)

“It is clear that capitalism has led to the super-exploitation of women. This would not offer much consolation if it had only meant heightened misery and oppression, but fortunately it has also provoked resistance. And capitalism has become aware that if it completely ignores or suppresses this resistance it might become more and more radical, eventually turning into a movement for self-reliance and perhaps even the nucleus of a new social order.” – Robert Biel, The New Imperialism (2000)

“The emerging liberative agent in the Third World is the unwaged force of women who are not yet disconnected from the life economy by their work. They serve life not commodity production. They are the hidden underpinning of the world economy and the wage equivalent of their life-serving work is estimated at $16 trillion.” – John McMurtry, The Cancer State of Capitalism (1999)

“The pestle has snapped because of so much pounding. Tomorrow I will go home. Until tomorrow Until tomorrow… Because of so much pounding, tomorrow I will go home.” – Hausa women’s song from Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

This essay is a political reading of the restructuring of the (re)production of labor-power in the global economy, but it is also a feminist critique of Marx that, in different ways, has been developing since the 1970s. This critique was first articulated by activists in the Campaign for Wages For Housework, especially Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati, among others, and later by Ariel Salleh in Australia and the feminists of the Bielefeld school, Maria Mies, Claudia Von Werlhof, Veronica Benholdt-Thomsen.

This essay is a political reading of the restructuring of the (re)production of labor-power in the global economy, but it is also a feminist critique of Marx that, in different ways, has been developing since the 1970s. This critique was first articulated by activists in the Campaign for Wages For Housework, especially Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati, among others, and later by Ariel Salleh in Australia and the feminists of the Bielefeld school, Maria Mies, Claudia Von Werlhof, Veronica Benholdt-Thomsen.

At the center of this critique is the argument that Marx’s analysis of capitalism has been hampered by his inability to conceive of value-producing work other than in the form of commodity production and his consequent blindness to the significance of women’s unpaid reproductive work in the process of capitalist accumulation. Ignoring this work has limited Marx’s understanding of the true extent of the capitalist exploitation of labor and the function of the wage in the creation of divisions within the working class, starting with the relation between women and men.

Had Marx recognized that capitalism must rely on both an immense amount of unpaid domestic labor for the reproduction of the workforce, and the devaluation of these reproductive activities in order to cut the cost of labor power, he may have been less inclined to consider capitalist development as inevitable and progressive.

As for us, a century and a half after the publication of Capital, we must challenge the assumption of the necessity and progressivity of capitalism for at least three reasons.

I recently finished this fascinating book by C.L.R. James, detailing the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803. This was the first (and only?) time in history that an entire colony of African slaves revolted against their masters and succeeded in establishing independence. The magnitude of such a feat, considering all the European backlash and repression, from no less than Napoleon, is shocking to this day.

I recently finished this fascinating book by C.L.R. James, detailing the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803. This was the first (and only?) time in history that an entire colony of African slaves revolted against their masters and succeeded in establishing independence. The magnitude of such a feat, considering all the European backlash and repression, from no less than Napoleon, is shocking to this day.

C.L.R. James is famous for being one of the most outspoken anti-colonial Marxist thinkers of the 20th Century. His political career started in his native Trinidad, took him through Trotskyism to the Johnson-Forest Tendency, which defined the Soviet Union as state capitalist. After being deported from the US, he spent his final years living in London and married to Selma James, the influential Marxist feminist and founder of the Wages for Housework campaign.

The merits of this book are obvious, it is a blow-by-blow account of how the slaves of Saint-Domingue became the free citizens of Haiti. For its profound social history, it has become required reading for post-colonial theorists, pan-Africanists and anti-capitalists of all stripes. The book is made more relevant by the ongoing injustices against the Haitian people by the US government and international NGOs, which have kept Haiti in a state of poverty and dependence. It is important to remind ourselves that the Haitians are proud people with a history of self-empowerment.

The flaws of the book are perhaps more interesting. James wants to paint Toussaint L’Ouverture in the same stripe as Vladimir Lenin, who James sees as actually a heroic revolutionary leader. From this error stem all the peculiar sections of the book where Toussaint’s character become the main focus. Most interestingly, James also criticizes some of Toussaint’s worst moves, correctly charging them as cowardly or counter-revolutionary, yet does not hesitate to explain them away by referring to Toussaint’s “genius.”

For me the bottom line is that humans instinctively desire freedom. We don’t need any authorities to create it for us, we either all create it together or we lack it. Generals like Toussaint tend to want to appeal to authority, whether Napoleon or the bourgeois Jacobins in Paris. It is a simple fact that people in power are more concerned about what other people with power think, rather than what the people think. Here lies Toussaint’s mistake, and the mistake of Leninism as well.

None of this should discourage the reader from reading and absorbing the social history behind one of the greatest popular democratic victories of all time. The point is to read history critically.

One such critical reader is my friend Daniel, who wrote the excellent review which follows, and which brings the contradictions of James’ work to life. [alex]

The Black Jacobins

C.L.R. James, 1938

Review by Daniel Meltzer.

This book was an excellent read. The strengths included breathtaking battle scenes, rousing rhetoric for freedom and against slavery, brilliant stories of liberation, and page-turning political intrigue. The weaknesses in the book come from self-defeating politics of discipline for the sake of discipline, and the heart-rending compromises that Toussaint L’Overture makes with people who see him and the republic he created as nothing more than slaves to be punished for their insubordination.

Millions of slaves were stolen from Africa in bondage to work in Haiti. Most would die on the slave ships or in the fields.

The utter brutality and injustice of slave ownership, and the barbaric treatment of slaves is scandalous. You will literally shake your head at the stories of how slaves were treated under the law in Haiti. A particularly unnerving example is the slavemasters filling a slave up with gunpowder and lighting a fuse, exploding the body of the slave, perhaps for punishment, but seemingly just as often because the slavemasters could.

The slaves began creating a series of low-level daily resistance to such a situation that is tragic and fascinating. “The majority of the slaves accomodated themselves to this unceasing brutality by a profound fatalism and a wooden stupidity before their masters. […]Through the shirt of [a slave] a master can feel the potatoes which he denies he has stolen. They are not potatoes, he says, they are stones. He is undressed and the potatoes fall to the ground. “Eh! master. The devil is wicked. Put stones, and look, you find potatoes.” Read the rest of this entry »

Upheaval Productions has produced some impressive documentary and interview footage on the most pressing issues of our day. Here I am reposting 3 of their courageous interviews with 3 modern-day visionaries: Malalai Joya, a heroic voice of reason from the warzone of Afghanistan, Charles Bowden, who continues to shed necessary light on the underlying causes of US-Mexico border violence, drug trade and immigration, and George Katsiaficas, who has spent his life studying revolutions and popular uprisings around the world, and how ordinary people make positive social change.

Each video is about 10 minutes. I learned a lot from all three interviews, and I’m sure you will too. Enjoy!

Malalai Joya is an Afghan activist, author, and former politician. She served as an elected member of the 2003 Loya Jirga and was a parliamentary member of the National Assembly of Afghanistan, until she was expelled for denouncing other members as warlords and war criminals.

She has been a vocal critic of both the US/NATO occupation and the Karzai government, as well as the Taliban and Islamic fundamentalists. After surviving four assassination attempts she currently lives underground in Afghanistan, continuing her work from safe houses. After the release of her memoir, A Woman Among Warlords, she recently concluded a US speaking tour. She sat down for an interview with David Zlutnick while in San Francisco on April 9, 2011. Read the rest of this entry »

Republished by Energy Bulletin, The Todd Blog, OpEdNews, Countercurrents, and translated into Turkish for Hafif.org.

The following exchange between Michael Carriere and Alex Knight occurred via email, July 2010. Alex Knight was questioned about the End of Capitalism Theory, which states that the global capitalist system is breaking down due to ecological and social limits to growth and that a paradigm shift toward a non-capitalist future is underway.

This is the second part of a four-part interview. Scroll to the bottom for links to the other sections.

Part 2A. Capitalism and Ecological Limits

MC: Capitalism has faced many moments of crisis over time. Is there something different about the present crisis? What makes the end of capitalism a possibility now?

AK: This is such an important question, and it’s vital to think and talk about the crisis in this way, with a view toward history. It’s not immediately obvious why this crisis began and why, two years later, it’s not getting better. Making sense of this is challenging. Especially since knowledge of economics has become so enclosed within academic and professional channels where it’s off-limits to the majority of the population. Even progressive intellectuals, who aim to translate and explain the crisis to regular folks, too often fall into the trap of accepting elite explanations as the starting point and then injecting their politics around the edges. This is why there is such an abundance of essays and videos analyzing “credit default swaps”, “collateralized debt obligations,” etc., as if this crisis is about nothing more than greedy speculators overstepping their bounds.

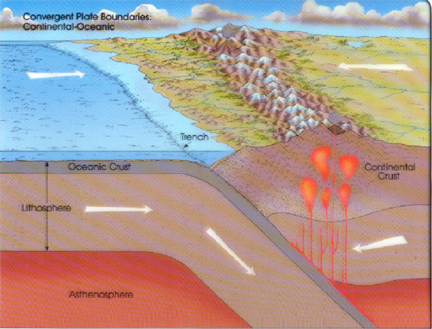

On the contrary, the End of Capitalism Theory insists there are deeper explanations for why this crisis is so severe, widespread, and long-lasting. Here’s one explanation: The devastating quaking of the financial markets, and the lingering aftershocks we’re experiencing in layoffs and cut-backs, are manifestations of much larger tectonic shifts under the surface of the economy. This turmoil originates from deep instabilities within capitalism, the global economic system that dominates our planet. The dramatic crisis we are experiencing now is resulting from a massive underground collision between capitalism’s relentless need for growth on one side, and the world’s limited capacity to sustain that growth on the other.

These limits to growth, like the continental plates, are enormous, permanent qualities of the Earth – they cannot be ignored or simply moved out of the way. The limits to growth are both ecological, such as shortages of resources, and social, such as growing movements for change around the globe. As capitalism rams into these limiting forces, numerous crises (economic, energy, climate, food, water, political, etc.) erupt, and destruction sweeps through society. This collision between capitalism and its limits will continue until capitalism itself collapses and is replaced by other ways of living.

Tectonic Plates Colliding - Capitalism is Ramming into the Limits to Growth, Causing Massive Shocks on the Surface of the Economy

The End of Capitalism Theory argues that capitalism will not be able to overcome these limits to growth, and therefore it is only a matter of time before we are living in a non-capitalist world. A paradigm shift towards a new society is underway. There’s a chance this new future could be even worse, but I hold tremendous hope in the capacity of human beings to invent a better life for themselves when given the chance. Part of my hope springs from the understanding that capitalism has caused terrible havoc all over the world through the violence it perpetrates against humanity and Mother Earth. The end of capitalism need not be a disaster. It can be a triumph. Or, perhaps, a sigh of relief.

Defining the Crisis

Rather than spend our time learning the language of Wall St. and trying to understand the economic crisis from the perspective of the bankers and capitalists, I think we can get much further if we take our own point of reference and then investigate below the surface to try to find the true origins of the crisis. This is what I call a common sense radical approach. Start from where we are, who we are, and what we know, because you don’t need to be an academic to understand the economy – you just need common sense. Then try to get to the root of the issue (radical coming from the Latin word for “root”). What is really going on under the surface? What is the core of the problem? If we can’t come up with a common sense radical explanation of the crisis, we’ll always be stuck within someone else’s dogma. This could be Wall St. dogma, Marxist dogma, Christian dogma, etc. So what is this crisis really about? Read the rest of this entry »

Child soldiers in the Congo Civil War

A civil war has been raging in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since.. well.. pretty much since the Belgians conquered the area, committed genocide, and called it a colony, as told in the excellent book King Leopold’s Ghost. But in the past 13 years, warfare has escalated and killed over 6 million Congolese, while rape has become an absolute epidemic and one of the main weapons of war. The UN’s top humanitarian official described the sexual violence against Congolese women as “almost unimaginable” for its frequency and ferocity.

This is a conflict that concerns us all, as it sheds crucial light on the functioning of global capitalism. At the center of the war is a mineral called coltan, short for Columbite-tantalite, which is used in capacitors, a necessary piece of electronics found in virtually every electronic device of modern capitalist society, from laptops to cell phones to cameras and jet engines. See Coltan: Learning the Basics. Coltan is just one of several expensive and rare minerals abundant in this remote region of central Africa, but coltan is ONLY available in this part of the world, which makes it extremely valuable.

Millions of children are exploited to mine coltan and other valuable minerals in the Congo

The DRC government, Uganda, Rwanda, and various militias and guerrilla forces are fighting over control of the land where these minerals are mined. The local residents, whose traditional lifestyles have been disrupted by decades of civil war, are forced to dig tiny amounts of these “conflict minerals” from the soil in inhuman conditions, often with their bare hands. An estimated 2 million of the miners are children, and often they are literal or virtual slaves who are on the brink of starvation. It is a situation which can only be described as hell on earth.

When you hear about such extreme exploitation, you can be pretty sure that some folks are making a hell of a lot of money. In this case, it’s western corporations like Nokia, Motorola, Compaq, Dell, IBM, Sony and many more who rely on extremely cheap capacitors in their electronics to make their profits from our Christmas presents. These companies have thus far avoided scrutiny by outsourcing the more direct business of extracting the minerals to smaller companies.

If there is any hope in this terrible situation, it is that capitalism is reaching the end of its ability to exploit the people of the world the way it has for the last centuries, and through the increased awareness of what is happening in places like the Congo, we as a people will say “Never again.” It is primarily the responsibility of those of us in the wealthy countries to put a stop to this paradigm of rape, slavery, and capitalist profit. Only we have the power to end the madness.

Below is a wonderful article that outlines specific solutions to the Congo civil war. [alex]

Conflict Minerals: A Cover For US Allies and Western Mining Interests?

Kambale Musavuli and Bodia Macharia

Originally published by Huffington Post, Dec. 14, 2009.

As global awareness grows around the Congo and the silence is finally being broken on the current and historic exploitation of Black people in the heart of Africa, myriad Western based “prescriptions” are being proffered. Most of these prescriptions are devoid of social, political, economic and historical context and are marked by remarkable omissions. The conflict mineral approach or efforts emanating from the United States and Europe are no exception to this symptomatic approach which serves more to perpetuate the root causes of Congo’s challenges than to resolve them.

The conflict mineral approach has an obsessive focus on the FDLR and other rebel groups while scant attention is paid to Uganda (which has an International Court of Justice ruling against it for looting and crimes against humanity in the Congo) and Rwanda (whose role in the perpetuation of the conflict and looting of Congo is well documented by UN reports and international arrest warrants for its top officials). Rwanda is the main transit point for illicit minerals coming from the Congo irrespective of the rebel group (FDLR, CNDP or others) transporting the minerals. According to Dow Jones, Rwanda’s mining sector output grew 20% in 2008 from the year earlier due to increased export volumes of tungsten, cassiterite and coltan, the country’s three leading minerals with which Rwanda is not well endowed. In fact, should Rwanda continue to pilfer Congo’s minerals, its annual mineral export revenues are expected to reach $200 million by 2010. Former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Herman Cohen says it best when he notes “having controlled the Kivu provinces for 12 years, Rwanda will not relinquish access to resources that constitute a significant percentage of its gross national product.” As long as the West continues to give the Kagame regime carte blanche, the conflict and instability will endure. Read the rest of this entry »

The efforts of these pirates to gain desperately-needed resources to escape the extreme poverty of Somalia by capturing vulnerable international shipping seem to be virtually unstoppable. As the article says, Somali pirates now hold about 12 different ships hostage, and this oil tanker (whose cargo is worth about $20 million) was captured some 800 miles off the coast of Somalia.

This constitutes yet another significant “social limit to growth” as I explain in my synopsis – people across the world are less and less willing, or able, to “play by the rules” of global capitalism, when they know the system isn’t working for them. The actions of the Somali pirates are just one dramatic and violent example of a much more generalized pattern of resistance, which is placing significant barriers to profit, and thereby opening up possibilities for new systems to emerge and replace capitalism. [alex]

Somali pirates hijack oil tanker headed to New Orleans

By The Associated Press, Published by Nola.com

November 30, 2009, 11:06AM

The Greece-flagged tanker Maran Centaurus, pictured here, was seized by Somali pirates on Sunday, Nov. 29, 2009. It was headed to New Orleans, according to a report in the New York Times.

The Greece-flagged Maran Centaurus was hijacked Sunday about 800 miles (1,300 kilometers) off the coast of Somalia, said Cmdr. John Harbour, a spokesman for the EU Naval Force. Harbour said it originated from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia and was destined for New Orleans, according to a report the New York Times.

The ship has 28 crew members on board, he said.

The shipping intelligence company Lloyd’s List said the Maran Centaurus is a “very large crude carrier, with a capacity of over 300,000 tons.”

Stavros Hadzigrigoris from the ship’s owners, Maran Tankers Management, said the tanker was carrying around 275,000 metric tons of crude. At an average price of around $75 a barrel, the cargo is worth more than $20 million. Hadzigrigoris declined to say who owned the oil.

Pirates have increased attacks on vessels off East Africa for the millions in ransom that can be had. Though pirates have successfully hijacked dozens of vessels the last several years, Sunday’s attack appears to be only the second ever on an oil tanker. Read the rest of this entry »

In 1995, multinational oil corporation Shell conspired with the Nigerian government to brutally suppress a popular nonviolent social movement that called for environmental justice in their polluted land. A key moment in this campaign of violence was the military show-trial of Ken Saro-Wiwa, leader of the Ogoni people and nonviolent advocate, which led to his execution.

Shell is currently facing trial in New York in a lawsuit brought by the Wiwa family, charging the oil company with “requesting, financing, and assisting the Nigerian military which used deadly force to repress opposition to Shell’s operations in the Ogoni region of the Niger Delta.”

This short video tells the story of Ken Saro-Wiwa and how corporate and state power merge to violently suppress grassroots social movements in order to protect the exploitation of the environment and workers.

Recent Comments