You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Iraq’ category.

This essay, written following a listening tour across the US, asks some of the most important questions facing social movements today, including “How Do We Build Intergenerational Movements?”, “What About Multiracial Movement Building?” and “How Do We Develop Strategy?”

I read this when it first came out in the summer of 2006 and it pretty much rocked my socks off and made me excited to get involved in the new SDS, so I figured I’d repost it for folks who never got to read it. [alex]

Ten Questions for Movement Building

by Dan Berger and Andy Cornell

Originally published by Monthly Review Zine.

For five weeks in the late spring of 2006, we toured the eastern half of the United States to promote two books — Letters From Young Activists: Today’s Rebels Speak Out (Nation Books, 2005) and Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity (AK Press, 2006) — and to get at least a cursory impression of sectors of the movement in this country. We viewed the twenty-eight events not only as book readings but as conscious political conversations about the state of the country, the world, and the movement.

Of course, such quick visits to different parts of the country can only yield so much information. Because this was May and June, we did not speak on any school campuses and were unable to gather a strong sense of the state of campus-based activism. Further, much of the tour came together through personal connections we’ve developed in anarchist, queer, punk, and white anti-racist communities, and, as with any organizing, the audience generally reflected who organized the event and how they went about it rather than the full array of organizing projects transpiring in each town. Yet several crucial questions were raised routinely in big cities and small towns alike (or, alternately, were elided but lay just beneath the surface of the sometimes tense conversations we were party to). Such commonality of concerns and difficulties demonstrates the need for ongoing discussion of these issues within and between local activist communities. Thus, while we don’t pretend to have an authoritative analysis of the movement, we offer this report as part of a broader dialogue about building and strengthening modern revolutionary movements — an attempt to index some common debates and to offer challenges in the interests of pushing the struggle forward.

Challenges and Debates:

The audiences we spoke with tended to be predominantly white and comprised of people self-identified as being on the left, many of whom are active in one or more organizations locally or nationally. We traveled through the Northeast (including a brief visit to Montreal), the rust belt, the Midwest, parts of the South, and the Mid-Atlantic. Some events tended to draw mostly 60s-generation activists, others primarily people in their 20s, and more than a few were genuinely intergenerational. Not surprisingly, events at community centers and libraries afforded more room for conversation than those at bookstores. Crowds ranged anywhere from 10 to 100 people, although the average event had about 25 people. Even where events were small gatherings of friends, they proved to be useful dialogues about pragmatic work. Our goals for the tour were: establishing a sense of different organizing projects; pushing white people in an anti-racist and anti-imperialist direction while highlighting the interrelationship of issues; and grappling with the difficult issues of organizing, leadership, and intergenerational movement building. The following ten questions emerge from our analysis of the political situation based on our travels and meetings with activists of a variety of ages and range of experiences.

1. What Is Organizing?

Every event we did focused on the need for organizing. This call often fell upon sympathetic ears, but was frequently met with questions about how to actually organize and build lasting radical organizations, particularly in terms of maintaining radical politics while reaching beyond insular communities. There are too few institutions training young or new activists in the praxis of organizing and anti-authoritarian leadership development. Read the rest of this entry »

Also published by The Rag Blog, OpEdNews, Signs of the Times, Interactivist Info Exchange, and Toward Freedom.

Who Were the Witches? – Patriarchal Terror and the Creation of Capitalism

Who Were the Witches? – Patriarchal Terror and the Creation of Capitalism

Alex Knight

November 5, 2009

This Halloween season, there is no book I could recommend more highly than Silvia Federici’s brilliant Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia 2004), which tells the dark saga of the Witch Hunt that consumed Europe for more than 200 years. In uncovering this forgotten history, Federici exposes the origins of capitalism in the heightened oppression of workers (represented by Shakespeare’s character Caliban), and most strikingly, in the brutal subjugation of women. She also brings to light the enormous and colorful European peasant movements that fought against the injustices of their time, connecting their defeat to the imposition of a new patriarchal order that divided male from female workers. Today, as more and more people question the usefulness of a capitalist system that has thrown the world into crisis, Caliban and the Witch stands out as essential reading for unmasking the shocking violence and inequality that capitalism has relied upon from its very creation.

Who Were the Witches?

Parents putting a pointed hat on their young son or daughter before Trick-or-Treating might never pause to wonder this question, seeing witches as just another cartoonish Halloween icon like Frankenstein’s monster or Dracula. But deep within our ritual lies a hidden history that can tell us important truths about our world, as the legacy of past events continues to affect us 500 years later. In this book, Silvia Federici takes us back in time to show how the mysterious figure of the witch is key to understanding the creation of capitalism, the profit-motivated economic system that now reigns over the entire planet.

During the 15th – 17th centuries the fear of witches was ever-present in Europe and Colonial America, so much so that if a woman was accused of witchcraft she could face the cruellest of torture until confession was given, or even be executed based on suspicion alone. There was often no evidence whatsoever. The author recounts, “for more than two centuries, in several European countries, hundreds of thousands of women were tried, tortured, burned alive or hanged, accused of having sold body and soul to the devil and, by magical means, murdered scores of children, sucked their blood, made potions with their flesh, caused the death of their neighbors, destroyed cattle and crops, raised storms, and performed many other abominations” (169).

In other words, just about anything bad that might or might not have happened was blamed on witches during that time. So where did this tidal wave of hysteria come from that took the lives so many poor women, most of whom had almost certainly never flown on broomsticks or stirred eye-of-newt into large black cauldrons?

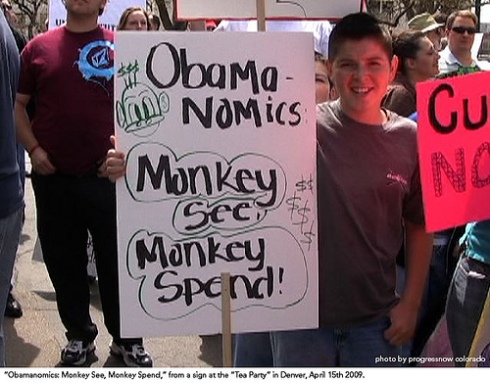

Caliban underscores that the persecution of witches was not just some error of ignorant peasants, but in fact the deliberate policy of Church and State, the very ruling class of society. To put this in perspective, today witchcraft would be a far-fetched cause for alarm, but the fear of hidden terrorists who could strike at any moment because they “hate our freedom” is widespread. Not surprising, since politicians and the media have been drilling this frightening message into people’s heads for years, even though terrorism is a much less likely cause of death than, say, lack of health care.1 And just as the panic over terrorism has enabled today’s powers-that-be to attempt to remake the Middle East, this book makes the case that the powers-that-were of Medieval Europe exploited or invented the fear of witches to remake European society towards a social paradigm that met their interests.

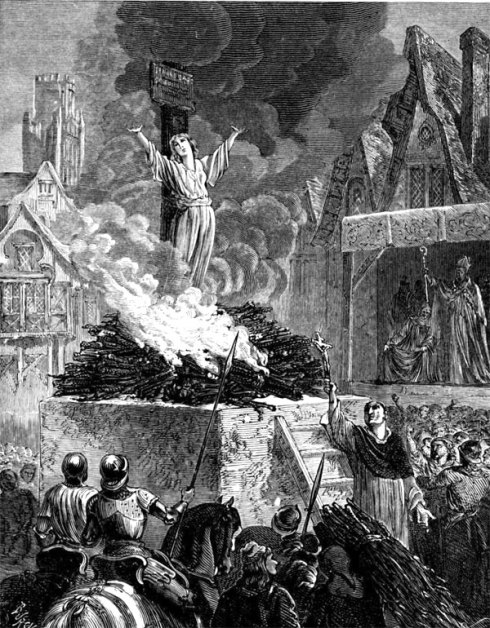

Interestingly, a major component of both of these crusades was the use of so-called “shock and awe” tactics to astound the population with “spectacular displays of force,” which helped to soften up resistance to drastic or unpopular reforms.2 In the case of the Witch Hunt, shock therapy was applied through the witch burnings – spectacles of such stupefying violence that they paralyzed whole villages and regions into accepting fundamental restructuring of medieval society.3 Federici describes a typical witch burning as, “an important public event, which all the members of the community had to attend, including the children of the witches, especially their daughters who, in some cases, would be whipped in front of the stake on which they could see their mother burning alive” (186).

The witch burning was the medieval version of "Shock and Awe"

The book argues that these gruesome executions not only punished “witches” but graphically demonstrated the repercussions for any kind of disobedience to the clergy or nobility. In particular, the witch burnings were meant to terrify women into accepting “a new patriarchal order where women’s bodies, their labor, their sexual and reproductive powers were placed under the control of the state and transformed into economic resources” (170). Read the rest of this entry »

After a wild but empowering week of demonstrations in Pittsburgh, here’s a short media recap of some of the highlights. [alex]

$12 Trillion has been given by the US government to large banks and corporations since last year

Great short news video on why the protesters were in Pittsburgh.

Exposes the police repression felt by the whole city last week, not just protesters.

The successes of mass protest.

IVAW held a press conference and action Friday morning about no longer sacrificing for war

Finally, see this audio report from Free Speech Radio News for more context.

Recent Comments