I recently finished this fascinating book by C.L.R. James, detailing the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803. This was the first (and only?) time in history that an entire colony of African slaves revolted against their masters and succeeded in establishing independence. The magnitude of such a feat, considering all the European backlash and repression, from no less than Napoleon, is shocking to this day.

I recently finished this fascinating book by C.L.R. James, detailing the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803. This was the first (and only?) time in history that an entire colony of African slaves revolted against their masters and succeeded in establishing independence. The magnitude of such a feat, considering all the European backlash and repression, from no less than Napoleon, is shocking to this day.

C.L.R. James is famous for being one of the most outspoken anti-colonial Marxist thinkers of the 20th Century. His political career started in his native Trinidad, took him through Trotskyism to the Johnson-Forest Tendency, which defined the Soviet Union as state capitalist. After being deported from the US, he spent his final years living in London and married to Selma James, the influential Marxist feminist and founder of the Wages for Housework campaign.

The merits of this book are obvious, it is a blow-by-blow account of how the slaves of Saint-Domingue became the free citizens of Haiti. For its profound social history, it has become required reading for post-colonial theorists, pan-Africanists and anti-capitalists of all stripes. The book is made more relevant by the ongoing injustices against the Haitian people by the US government and international NGOs, which have kept Haiti in a state of poverty and dependence. It is important to remind ourselves that the Haitians are proud people with a history of self-empowerment.

The flaws of the book are perhaps more interesting. James wants to paint Toussaint L’Ouverture in the same stripe as Vladimir Lenin, who James sees as actually a heroic revolutionary leader. From this error stem all the peculiar sections of the book where Toussaint’s character become the main focus. Most interestingly, James also criticizes some of Toussaint’s worst moves, correctly charging them as cowardly or counter-revolutionary, yet does not hesitate to explain them away by referring to Toussaint’s “genius.”

For me the bottom line is that humans instinctively desire freedom. We don’t need any authorities to create it for us, we either all create it together or we lack it. Generals like Toussaint tend to want to appeal to authority, whether Napoleon or the bourgeois Jacobins in Paris. It is a simple fact that people in power are more concerned about what other people with power think, rather than what the people think. Here lies Toussaint’s mistake, and the mistake of Leninism as well.

None of this should discourage the reader from reading and absorbing the social history behind one of the greatest popular democratic victories of all time. The point is to read history critically.

One such critical reader is my friend Daniel, who wrote the excellent review which follows, and which brings the contradictions of James’ work to life. [alex]

The Black Jacobins

C.L.R. James, 1938

Review by Daniel Meltzer.

This book was an excellent read. The strengths included breathtaking battle scenes, rousing rhetoric for freedom and against slavery, brilliant stories of liberation, and page-turning political intrigue. The weaknesses in the book come from self-defeating politics of discipline for the sake of discipline, and the heart-rending compromises that Toussaint L’Overture makes with people who see him and the republic he created as nothing more than slaves to be punished for their insubordination.

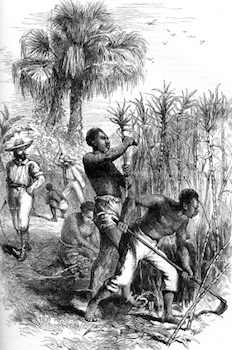

Millions of slaves were stolen from Africa in bondage to work in Haiti. Most would die on the slave ships or in the fields.

The utter brutality and injustice of slave ownership, and the barbaric treatment of slaves is scandalous. You will literally shake your head at the stories of how slaves were treated under the law in Haiti. A particularly unnerving example is the slavemasters filling a slave up with gunpowder and lighting a fuse, exploding the body of the slave, perhaps for punishment, but seemingly just as often because the slavemasters could.

The slaves began creating a series of low-level daily resistance to such a situation that is tragic and fascinating. “The majority of the slaves accomodated themselves to this unceasing brutality by a profound fatalism and a wooden stupidity before their masters. […]Through the shirt of [a slave] a master can feel the potatoes which he denies he has stolen. They are not potatoes, he says, they are stones. He is undressed and the potatoes fall to the ground. “Eh! master. The devil is wicked. Put stones, and look, you find potatoes.”

There is also a peculiar living of the slaves when they are so close to brutal death. The phenomenon of poisoning struck me particularly, which was apparently quite commonplace in Haiti before the revolution. Slaves used poison to alleviate their slavery at great expense of human life. Revenge poisoning by a slave of a slave master was common, as was the avoidance of splitting up families by poisoning all but one son of a slavemaster so that there would be but one heir. But so was other, more insidious poisonings. If it was heard that a master was to undertake more ambitious plantations, the slaves would poison one another until the numbers had been reduced to where such an undertaking would be impossible, in order to keep their workload down. Or if a kinder master were leaving town, some of the slaves and the property (cattle) would be poisoned, so that the master would have to stay to sort out the mess.

It is no wonder, given the ferocity of life for a slave, that when they organized insurrection, not just day-to-day resistance, they were ferocious themselves. I was dazzled by haunting images of the oppressed Haitians finding their revenge. “The slaves destroyed tirelessly[…]they were seeking their salvation in the most obvious way, the destruction of what they knew was the cause of their sufferings; and if they destroyed much it was because they suffered much. […] “Vengeance! Vengeance!” was their war-cry, and one of them carried a white child on a pike as a standard. And yet they were surprisingly moderate, then and afterwards, far more humane than their masters had been or would ever be to them.”

Before the revolution, Saint-Domingue was the richest colony in the world. “Of the half-million slaves in the colony in 1789, more than two-thirds had been born in Africa.”

One particular passage left me breathless: that of Hyacinth. “Hyacinth, a bull’s tail in his hand, ran from rank to rank crying that his talisman would chase death away. He charged at [the French] head, passing unscathed through the bullets and the grape-shot. Under such leadership the Africans were irrisistible. They clutched at the horses of the dragoons, and pulled off the riders. They put their arms down into the mouths of cannon in order to pull out the bullets and called to their comrades “Come, come, we have them.” The cannon were discharged and blew them to pieces. But others swarmed over guns and gunners, threw their arms around them and silenced them.”

Very quickly, the narrative of the Haitian Revolution is made into the narrative of Toussaint L’Overture. Toussaint’s nickname and eventually surname, means “the opening,” which refers to the skilled general’s ability to tear holes through the lines of the French forces in the initial battles of the Haitian anti-colonial war, but also to the fact that he, like the author of this review, has a gap between his front two teeth. This is an adorable factoid.

There was much colonial political intrigue that I wasn’t expecting. The slaves initially fought the French, and Toussaint allied himself with the Spaniards, the enemy of his enemy. England, smarting from a recent defeat in North America, also wanted new colonies. Spain had the best offer on the table, so the Haitian slaves fought both the French and the English. Then a revolution broke out in France, and the new republic abolished slavery and held that the Haitian slaves deserved freedom, a much stronger sentiment than Spain’s promises. Toussaint and the slaves did a dramatic 180 degree turn, conquering the lands won for Spain back for the new French Republic, returning Spanish lands to France, losing land to the English, whom Toussaint expended a great deal of energy expelling from the colony.

As the French revolution turned sour and the Jacobins were replaced by the Napoleonic forces of reaction, Toussaint and his slave army attempted to stay loyal to France. But Napoleon had no use for a colony without slavery, and Toussaint’s slave army was forced to negotiate secretly with the English and fight off the French again, while the Spanish eagerly looked for a chance to take over. It was a pretty tense relationship with the major powers of Europe.

This was not the book I thought it would be. In ignorance, I had thought of the title of the book as an analogy, where the Haitian revolutionaries were akin to the Jacobins in France. As it turns out, Toussaint and his followers were in constant contact with the Jacobins, and saw themselves as fighting for the Jacobin revolution in France in one of France’s colonies. This social revolution in France is borne out in Haiti.

Unfortunately, the book spent a great deal of time describing Toussaint L’Overture avoiding social revolution, and attempting stability on the shakiest ground with conniving politicians that wished to see him back in chains. Toussaint was a brilliant general, to be sure, but he wanted to be a brilliant diplomat as well. This might have seemed practical at the time, but does not make for exciting reading, and is certainly not good revolutionary policy.

Every inch that Toussaint gave, the French took a foot, and insulted the bravery of the slave army. Toussaint began to mold himself to the wishes of these conniving politicians, and this was especially distressing. He even went as far as executing his cousin Moises, who was leading insurrection against the French at a time when Toussaint was attempting to make conciliations that would have deeply compromised the freedom he had already won for his people. It is in these moments of weakness and betrayal that “the masses looked on, confused, bewildered, not knowing what to do.”

“If [the slaves] had had the slightest material interest in the plantations, they would not have destroyed so wantonly. But they had none.”

.

CLR James spends an unfortunate amount of time praising the discipline of the slave army in not destroying the material conditions that kept them in slavery. Though slavery was abolished, in order to prevent in the slaves the “slip into the practice of cultivating just a small patch of land, producing just sufficient for their needs,” Toussaint “confined the blacks to the plantations under rigid penalties,” with practices not unlike later feudalism, where a quarter of the produce was given to the laborers. “Toussaint knew the backwardness of the laborers; he made them work.” “Losing sight of his mass support, taking it for granted, he sought only to conciliate the whites at home and abroad.” There are also several remarks as to the discipline of the former slaves in not destroying property, when it was property that kept them enslaved. I am not impressed by morose discipline for the sake of discipline.

.

CLR James wished to see in Toussaint and the Haitian revolution a Lenin figure, and Toussaint at his weakest, was able to give him that satisfaction.

The book takes a turn for the better just before the end, as the clutter of diplomacy with slaveowners and the compromise for the sake of discipline gave way to yet another war with France in the Haiti’s war for independence. “Neither Dessalines’ army nor his ferocity won the victory. It was the people. They burned San Domingo flat so that at the end of the war it was a charred desert. […”]We have a right to burn what we cultivate because a man has a right to dispose of his own labor, was the reply of this unknown anarchist.[“]” “It was a people’s war. They played the most audacious tricks on the French. [A French officer] heard at a musket’s distance a low voice psaying “Platoon, halt! To the right, dress!” The French made their dispositions and waited all night for a sudden attack. When the day came, they found that they had been the dupe of about a hundred laborers. “These ruses, if one paid too much attention to them, destroyed one’s morale; if they were neglected, they could lead to surprises.”

The people of Haiti fought fiercely, not just with their lives, but with their deaths for freedom. “When Chevalier, a black chief, hesitated at the sight of the scaffold, his wife shamed him. “You do not know how sweet it is to die for liberty!” And refusing to allow herself to be hanged by the executioner, she took the rope and hanged herself.”

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article