You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Occupy’ category.

We’re almost four years into the 20s and the sooner we bring back the concept of decades the better. Decades give people, especially young people, a temporal identity and a grounding in history. Decades emphasize the importance of now, but also connect us to the past in a way that doesn’t alienate us from our elders or youths in the way the concept of “generations” does automatically. Decades are a key element of narrative storytelling, encourage critical thinking through comparing/contrasting eras, and make it easier to discuss the future. In sum, decades benefit mental health, social inclusion and connection, movement building, and resistance to the aimless void of late capitalism. Our ability to exercise historical agency and preserve historical memory may depend on us reviving this concept.

If you’re 35 or older, you remember the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s as regular talking points. Both in the historical sense of “what was the spirit of the 60s?” and in the future-focused sense of “this will be THE trend of the 90s.” The concept of decades permeated regular conversation, tying people together and rooting them in a temporal home, whether you were talking about music, sports, film, fashion, politics, games, or literally anything. It made it natural and popular to compare eras of things, which is a basic building block of both historical study as well as critical thinking itself. It also helped people form an identity, in the sense of “I’m a child of the 70s” – one shorthand reference point that contains a vast easily-recalled cultural context filled with people, events, products, art, styles, and social struggles. It was a source of pride to be associated with a decade.

When Y2K hit, the computers were just fine. Better than ever, in fact. But we weren’t, because we suddenly lost a very powerful tool for understanding our social environment. Without the concept of decades, we wandered into an amorphous fog without beginning or end, where we became easy-pickings for a consumer capitalism that thrives by developing isolated, disoriented worker-spectators. When ignorant of our past and uninterested in our future, we rarely make trouble for the ruling class.

At first, some people resisted the change. They coined names for the decade-to-be, but none caught on. They sounded forced, so they were relegated to the realm of jokes (Try to have a serious conversation about “the noughties”). Nothing stepped in to bridge the chasm.

It wasn’t a huge problem at first, because the 90s were such a recent frame of reference, so we could keep the concept of decades alive by just filing the present under “post-90s” or “this decade.” All the conversations we were accustomed to, where we compared trends in pants, or hair, or anarchist politics, kept rolling for a while, they just had this weird stand-in where you’d have to compare previous decades to the vague concept of “now.” As in, “you guys had VCRs in the 80s, but now we have the far-superior technology of DVD players, which will remain popular forever.”

Ten years passed. A new decade was scheduled to be starting, but no one took notice. The concept of decades wasn’t revived. Instead, it faded into oblivion. Maybe we were too buried under the infinite scroll of social media, our heads down, absorbed by our smartphones, or too obsessed by the latest streaming content, that we lost the ability to form long-range narratives. Our shared experience of the era itself began to fracture, as our attention scattered into increasingly fragmented niches of the spectacle, which concealed the fact that we were largely all doing the same thing at the same time. Or maybe we were so emotionally beaten down by the seemingly endless “War on Terror” and apocalyptic ecological catastrophe that we simply didn’t have the energy to think of ourselves as historical agents, and therefore couldn’t be bothered with putting a name on the era we were living through, even though “the teens” was an obvious and pleasant choice.

It’s not as if there weren’t massive and historically-important movements for social change happening in that decade. From the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter to MeToo to Transgender visibility, millions of people were organizing, shifting social norms, and becoming empowered to radically improve society in ways perhaps more profound than we know. But compared to movements of the 60s, 70s, 80s, or 90s, these new movements are unusually obscured, and perhaps in danger of being overlooked.

Organizers of these world-changing efforts – people like Alicia Garza and Marisa Holmes – should be recognized and remembered for their actions. Even more importantly, our understanding of how that decade’s movements arose, why they were so effective, and also what their shortcomings were, should be the topic of regular conversation so that we may improve upon them in the future. Yet, it’s nearly impossible to have a productive, civil version of such a discussion on social media, and it may be nearly impossible for a social movement in this day and age to outlast the ephemeral confines of a hashtag.

This is not to suggest that these movements will be forgotten, or to downplay the excellent work of the chroniclers of these efforts, who have produced worthwhile books, documentaries, and other media that actively preserve this historical memory. Instead, I suggest it is unfair to those culture-defining social movements that we can’t immediately recall their powerful messages, images, and actors through a universally-agreed-upon phrase like “the teens” in the same way that “the 60s” immediately conjures such thoughts of the Civil Rights Movement or the anti-Vietnam War movement.

By the way, don’t give me this crap about “generations.” The Civil Rights Movement/Black Freedom Struggle was driven forward by people of all ages, from elders like A. Philip Randolph to middle-aged people like Ella Baker, to children like those who walked out of school to pack the Birmingham jails. As far as I’m aware, the fear-mongering associated with “rebellious youth” has always existed. For sure it existed in the 60s, when the mass media did their best to demonize the anti-authoritarian, hopelessly “feminized” “Baby Boomers”, effectively blaming young people for everything wrong with the world. We’ve come full circle today, blaming those same people, who are now old, for the exact opposite reasons.

“Generations” are a fake conceptual tool used to divide people. Since 2000, as the concept of decades has fallen away, in part it has been superseded by the nefarious concepts of “Millennials” and “Gen. Z.” These are identities which are inherently exclusive, and usually they are invoked for purely negative characterizations. Eventually, “Gen. Z” will get the same scorn that “Boomers” do now, and it will be just as baseless.

In contrast, decades are inherently inclusive. Everyone who was alive in the 90s can reminisce about what that decade was like for them. Even if our experiences were vastly different, we can find common ground through cultural touchstones like The Simpsons or Tupac. That kind of conversation is not just idle nostalgia. It is a collective remembering that allows us to form social bonds with neighbors, co-workers, and fellow activists, to each of whom the 90s is a small building block in their own identity-formation.

If you read comments on Youtube under videos of old music or TV shows (and I’m not recommending you do), you’ll regularly see people lamenting that we no longer live in the [insert decade here]. Some of those commenters are old and feeling nostalgic for the loss of their youth. That’s normal. But some of those commenters are young. They will often mention that they “just turned 16” (or another age of fragile identity-formation). And yet, here they are, wandering the interwebs, watching videos that were produced before they were born and wishing they could time-travel back to the 20th century.

Meanwhile, the 21st century is nearly a quarter complete, and its music and TV shows have been equally valuable, if not more so. But without the decades providing an automatic frame of reference for great artistic works, we struggle to recall exactly when they were released, or how they related to concurrent events in society or technology, or even our own lives. Without decades, people don’t know how to talk to each other about their own time period. And so they don’t. They just slowly forget, as everything is enveloped in a nebulous, meaningless haze.

What stories are children of this century learning about their own time, and where they fit in? What can they be proud of? What can they look forward to?

There’s a bunch of things we could do for a better future for all. Redistributing the wealth of the top 1%. Replacing the private automobile with free public transit. Dismantling the prison-industrial complex in favor of systems of transformative justice and accountability. Planting a billion trees. Those will take a lot of hard work and a long time.

One thing that would take very little effort, would bring us into connection with those around us of all ages, would help us cherish the present and look forward to the future, would empower us to find meaning and feel better, is to reintroduce the concept of decades. We can start now, by acknowledging publicly, and habitually, that we live in the 20s.*

* I mean no disrespect to the decade of the 1920s, a fine decade to study and discuss. But of the decades called “the 20s”, the current decade is far more relevant to everyone living today and for the rest of the 21st century. I don’t know at what point people stopped referring to the 1820s as “the 20s,” but surely it was before 1923.

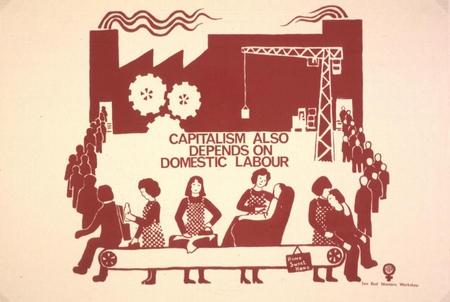

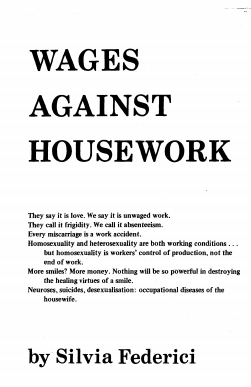

Silvia Federici is one of the most important political theorists alive today. Her landmark book Caliban and the Witch demonstrated the inextricable link between anti-capitalism and radical feminist politics by digging deep into the actual history of capital’s centuries-long attack on women and the body.

In this essay, originally written in 2008, she follows up on that revelation by laying out her feminist anti-capitalist vision, and how it extends beyond traditional Marxism. This piece is comprehensive – long but far-reaching. At times seeing the truth requires seeing in the dark – acknowledging the true horrors of the world as it currently is manifest.

This essay was updated and published in Silvia’s new anthology Revolution at Point Zero, and I have made a few small additional edits. Enjoy! [alex]

The Reproduction of Labor Power in the Global Economy and the Unfinished Feminist Revolution (2011 edition)

“Women’s work and women’s labor are buried deeply in the heart of the capitalist social and economic structure.” – David Staples, No Place Like Home (2006)

“Women’s work and women’s labor are buried deeply in the heart of the capitalist social and economic structure.” – David Staples, No Place Like Home (2006)

“It is clear that capitalism has led to the super-exploitation of women. This would not offer much consolation if it had only meant heightened misery and oppression, but fortunately it has also provoked resistance. And capitalism has become aware that if it completely ignores or suppresses this resistance it might become more and more radical, eventually turning into a movement for self-reliance and perhaps even the nucleus of a new social order.” – Robert Biel, The New Imperialism (2000)

“The emerging liberative agent in the Third World is the unwaged force of women who are not yet disconnected from the life economy by their work. They serve life not commodity production. They are the hidden underpinning of the world economy and the wage equivalent of their life-serving work is estimated at $16 trillion.” – John McMurtry, The Cancer State of Capitalism (1999)

“The pestle has snapped because of so much pounding. Tomorrow I will go home. Until tomorrow Until tomorrow… Because of so much pounding, tomorrow I will go home.” – Hausa women’s song from Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

This essay is a political reading of the restructuring of the (re)production of labor-power in the global economy, but it is also a feminist critique of Marx that, in different ways, has been developing since the 1970s. This critique was first articulated by activists in the Campaign for Wages For Housework, especially Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati, among others, and later by Ariel Salleh in Australia and the feminists of the Bielefeld school, Maria Mies, Claudia Von Werlhof, Veronica Benholdt-Thomsen.

This essay is a political reading of the restructuring of the (re)production of labor-power in the global economy, but it is also a feminist critique of Marx that, in different ways, has been developing since the 1970s. This critique was first articulated by activists in the Campaign for Wages For Housework, especially Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Selma James, Leopoldina Fortunati, among others, and later by Ariel Salleh in Australia and the feminists of the Bielefeld school, Maria Mies, Claudia Von Werlhof, Veronica Benholdt-Thomsen.

At the center of this critique is the argument that Marx’s analysis of capitalism has been hampered by his inability to conceive of value-producing work other than in the form of commodity production and his consequent blindness to the significance of women’s unpaid reproductive work in the process of capitalist accumulation. Ignoring this work has limited Marx’s understanding of the true extent of the capitalist exploitation of labor and the function of the wage in the creation of divisions within the working class, starting with the relation between women and men.

Had Marx recognized that capitalism must rely on both an immense amount of unpaid domestic labor for the reproduction of the workforce, and the devaluation of these reproductive activities in order to cut the cost of labor power, he may have been less inclined to consider capitalist development as inevitable and progressive.

As for us, a century and a half after the publication of Capital, we must challenge the assumption of the necessity and progressivity of capitalism for at least three reasons.

This personal reflection was written for and performed at a spoken word event on March 2nd in Philadelphia.

“After the Apocalypse” – by Alex Knight

As I write, it’s March 1, 2013. I never expected to see this date arrive.

As I write, it’s March 1, 2013. I never expected to see this date arrive.

When I was 10 or 11, my father and I watched a TV special, probably on FOX, called “Prophecies Revealed,” which rounded up an assortment of fables from Nostradomus on down, to scare the crap out of the audience and get ratings by making people believe the end of the world was right around the corner. One segment talked about the Mayan calendar, and over a background of creepy and violent images, posed the question, “what’s going to happen on December 21, 2012? Will our technologies revolt against us? Will there be some kind of cataclysmic event, like an enormous meteor impact? Will nuclear war finally consume the Earth?”

I feel silly to admit it, but these ideas of imminent doom really stuck with me. Maybe I was just an impressionable kid who had seen too many Terminator movies. Or maybe there is something really appealing, even liberating, about apocalypse – at least for those of us living in a repressive, alienating, hierarchal social system such as zombie-capitalism. The specter of apocalypse seems to substitute in negative form for the positive vision of “social revolution” that radicals a century ago believed in – namely, a way out, an escape. Say what you will about the Rapture – at least it’s a rupture. Meaning, even if the fires of armageddon were a nightmare in the short run, at least the horror of the world we live in would come to an end, and then maybe something better would sprout from the ashes.

Almost immediately after I left home for college, these apocalyptic prophecies were resurrected from the nether-regions of my mind. On September 11th, the World Trade Center and Pentagon were hit by hijacked airplanes. As I watched in my Freshman dormroom, I felt shock, sadness, but also a forbidden and shameful giddiness. The attack was a horrible, evil thing, and I feel awful for those who lost loved ones. But for me at age 18, the dramatic realness of that event was a sharp, sudden puncture to the bubbly propaganda image of 1990’s peaceful hegemonic America. It was the first time I ever realized that the world is not static – it is changing all the time. I had just never looked outside my plastic suburban cage to see the real world, in its full ugliness and beauty. September 11th, as hellish as it was, was for me that rupture – it jarred me into the awareness that there is an exit from the prison of mainstream America, if you’re willing to do a little digging.

I started to listen a bit more to my communist English teacher, be less defensive in response to voices critical of capitalism, and I set off down the rabbit hole. As Bush put the country on the warpath, I transformed myself from a video game junkie into a committed activist devoting every bit of energy I could to making revolution happen in this country, starting by organizing a national student movement against the war, I hoped. Read the rest of this entry »

[There are a lot of thought-provoking ideas in this article, as we reflect on the Occupy movement, what it was, what it meant, and where we go from here in our movements against zombie-capitalism and for a better world.

I intend to write much more about my reflections on Occupy, don’t worry. – alex]

Originally posted on Bay of Rage (May 16, 2012) (broken link 5/28).

THE COMMUNE

THE COMMUNE

For those of us in Oakland, “Occupy Wall Street” was always a strange fit. While much of the country sat eerily quiet in the years before the Hot Fall of 2011, a unique rebelliousness that regularly erupted in militant antagonisms with the police was already taking root in the streets of the Bay. From numerous anti-police riots triggered by the execution of Oscar Grant on New Year’s Day 2009, to the wave of anti-austerity student occupations in late 2009 and early 2010, to the native protest encampment at Glen Cove in 2011, to the the sequence of Anonymous BART disruptions in the month before Occupy Wall Street kicked off, our greater metropolitan area re-emerged in recent years as a primary hub of struggle in this country. The intersection at 14th and Broadway in downtown Oakland was, more often than not, “ground zero” for these conflicts.

If we had chosen to follow the specific trajectory prescribed by Adbusters and the Zucotti-based organizers of Occupy Wall Street, we would have staked out our local Occupy camp somewhere in the heart of the capitol of West Coast capital, as a beachhead in the enemy territory of San Francisco’s financial district. Some did this early on, following in the footsteps of the growing list of other encampments scattered across the country like a colorful but confused archipelago of anti-financial indignation. According to this logic, it would make no sense for the epicenter of the movement to emerge in a medium sized, proletarian city on the other side of the bay.

We intentionally chose a different path based on a longer trajectory and rooted in a set of shared experiences that emerged directly from recent struggles. Vague populist slogans about the 99%, savvy use of social networking, shady figures running around in Guy Fawkes masks, none of this played any kind of significant role in bringing us to the forefront of the Occupy movement. In the rebel town of Oakland, we built a camp that was not so much the emergence of a new social movement, but the unprecedented convergence of preexisting local movements and antagonistic tendencies all looking for a fight with capital and the state while learning to take care of each other and our city in the most radical ways possible.

This is what we began to call The Oakland Commune; that dense network of new found affinity and rebelliousness that sliced through seemingly impenetrable social barriers like never before. Our “war machine and our care machine” as one comrade put it. No cops, no politicians, plenty of “autonomous actions”; the Commune materialized for one month in liberated Oscar Grant Plaza at the corner of 14th & Broadway. Here we fed each other, lived together and began to learn how to actually care for one another while launching unmediated assaults on our enemies: local government, the downtown business elite and transnational capital. These attacks culminated with the General Strike of November 2 and subsequent West Coast Port Blockade.

Yesterday I had the honor of speaking alongside George Caffentzis to answer the question, “What is Capitalism?” Certainly this is one of the core questions of our era, as millions of people are becoming politicized during the unending economic crisis and looking for an analysis that can explain what is happening to them. In order to make a better world, we first need to define the system that dominates the current one, and that is capitalism.

Yesterday’s packed event was the first in Occupy Philadelphia‘s ten-part educational series “Dissecting Capitalism.” It was audio and video recorded, the audio is already online HERE. Listen in!

[update 2/13: and here is the video of the talk, in two parts!]

Part 2:

Below is the outline I created for my talk (downloadable HERE). I tried to bring a holistic analysis of the system that could be understandable by the average person, but still contain a nuanced perspective of all the ways capitalism has screwed us over and screwed over our planet. I’ll be fleshing this out over the next several days to revamp the “What is Capitalism?” section of the website. [alex]

What is Capitalism?

“Know Your Enemy” – Rage Against the Machine

2/1/2012 – LAVA

Alex Knight, endofcapitalism.com

- Capitalism is a Global System of Abuse

- Common Sense Radicalism – speak to the core issue in a way everyone can emotionally understand

- How does it feel to live in a capitalist system? Like an abusive relationship.

- “The problem that has no name.”

- Social and ecological trauma

- BP Oil Disaster demonstrates system’s logic: profit over all, total lack of accountability

- Power, Abuse, Resistance

- Power-Over and Power-With

- Internalized Oppression vs. Inherent Need for Self-determination

- Systems of Abuse/Oppression: Patriarchy, White Supremacy, Class

- Some Features of Class Societies:

- Inequality – the few benefit at the expense of the many

- Economic production disconnected from human need

- Forced labor – slavery, wage slavery

- State violence – punishment, repression

- Warfare, Conquest

- Propaganda

- Unsustainable ecological abuse

- Popular resistance

- Capitalism is the most advanced Class Society

- Capitalism: Pyramid of Accumulation

- Financial Speculation

- Commodity Trading, Commodities

- Wage Labor, Wage Labor, Wage Labor

- Enclosures: the largest, but invisible part of the iceberg

- any energy, resources or labor taken by force or without just compensation

- Stages of Capitalism: 1492 – Present

the following 12 songs were written/compiled by me for the People’s Victory Parade, hosted by Occupy Philly on 12/31/11.

they’re mostly Christmas/holiday tunes transformed into Occu-Carols, with a couple others thrown in as well. my favorite is #6 “Do You Hear What I Hear?”

let’s be a movement that sings!

alex

OCCUPY PHILLY SONGBOOK

1. WE WISH FOR A REVOLUTION

(by Alex Knight to the tune of “We Wish You a Merry Christmas”)

We wish for a revolution

We wish for a revolution

We wish for a revolution

In the coming New Year!

Tunisia was first

Egypt heard the call

Then Occupy Wall St.

Inspired us all.

(Chorus)

In Chile and Greece

Now Russia we see

The people are rising

For democracy.

(Chorus)

Now Philly has joined

We’re ready to rock

We’re just getting started

And we’ll never stop!

We wish for a revolution

We wish for a revolution

We wish for a revolution

In the coming New Year!

2. THE TWELVE DAYS OF OCCUPY

(inspired by other versions, including one by Gina Botel)

On the first day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

A tent and a community.

On the second day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Two woolen blankets and…

On the third day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Three warm meals…

On the fourth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Four clarifying questions…

On the fifth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

FIVE LONG GA’s…

On the sixth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Six working groups…

On the seventh day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Seven drummers drumming…

On the eighth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Eight signs a-painting…

On the ninth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Nine marchers marching…

On the tenth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Ten locked arms…

On the eleventh day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Eleven cops a-raiding…

On the twelfth day of Occupy, my new friends gave to me

Twelve new encampments… Read the rest of this entry »

I’ve been meaning to post this for a while! It’s a great short essay / pamphlet on race and racism, written for the Occupy movement. Please read! Race is an issue we ignore at our own peril. [alex]

Whiteness and the 99%

By Joel Olson

Originally published by Bring the Ruckus, 10/20/11. A printable PDF of this piece is available for download here, and a readable PDF is available here.

Occupy Wall Street and the hundreds of occupations it has sparked nationwide are among the most inspiring events in the U.S. in the 21st century. The occupations have brought together people to talk, occupy, and organize in new and exciting ways. The convergence of so many people with so many concerns has naturally created tensions within the occupation movement. One of the most significant tensions has been over race. This is not unusual, given the racial history of the United States. But this tension is particularly dangerous, for unless it is confronted, we cannot build the 99%. The key obstacle to building the 99% is left colorblindness, and the key to overcoming it is to put the struggles of communities of color at the center of this movement. It is the difference between a free world and the continued dominance of the 1%.

Left colorblindess is the enemy

Left colorblindness is the belief that race is a “divisive” issue among the 99%, so we should instead focus on problems that “everyone” shares. According to this argument, the movement is for everyone, and people of color should join it rather than attack it.

Left colorblindness claims to be inclusive, but it is actually just another way to keep whites’ interests at the forefront. It tells people of color to join “our” struggle (who makes up this “our,” anyway?) but warns them not to bring their “special” concerns into it. It enables white people to decide which issues are for the 99% and which ones are “too narrow.” It’s another way for whites to expect and insist on favored treatment, even in a democratic movement.

As long as left colorblindness dominates our movement, there will be no 99%. There will instead be a handful of whites claiming to speak for everyone. When people of color have to enter a movement on white people’s terms rather than their own, that’s not the 99%. That’s white democracy.

The white democracy

Biologically speaking, there’s no such thing as race. As hard as they’ve tried, scientists have never been able to define it. That’s because race is a human creation, not a fact of nature. Like money, it only exists because people accept it as “real.” Races exist because humans invented them.

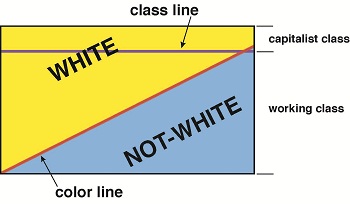

Why would people invent race? Race was created in America in the late 1600s in order to preserve the land and power of the wealthy. Rich planters in Virginia feared what might happen if indigenous tribes, slaves, and indentured servants united and overthrew them. So, they cut a deal with the poor English colonists. The planters gave the English poor certain rights and privileges denied to all persons of African and Native American descent: the right to never be enslaved, to free speech and assembly, to move about without a pass, to marry without upper-class permission, to change jobs, to acquire property, and to bear arms. In exchange, the English poor agreed to respect the property of the rich, help them seize indigenous lands, and enforce slavery.

This cross-class alliance between the rich and the English poor came to be known as the “white race.” By accepting preferential treatment in an economic system that exploited their labor, too, the white working class tied their wagon to the elite rather than the rest of humanity. This devil’s bargain has undermined freedom and democracy in the U.S. ever since.

The cross-class alliance that makes up the white race.

The cross-class alliance that makes up the white race.

As this white race expanded to include other European ethnicities, the result was a very curious political system: the white democracy. The white democracy has two contradictory aspects to it. On the one hand, all whites are considered equal (even as the poor are subordinated to the rich and women are subordinated to men). On the other, every white person is considered superior to every person of color. It’s democracy for white folks, but tyranny for everyone else. Read the rest of this entry »

A very useful article showing how the needs of people to be heard, to listen, and to have their voices count for something, are met through the General Assembly process of the Occupy movement. [alex]

A Therapist Talks About the Occupy Wall Street Events

Originally published by In Front and Center.

Last night I was talking with a group of activists/organizers from around the country about their impressions of the OWS movement. They were curious how the insights of a therapist and conflict facilitator schooled in Worldwork (which was developed by Arnold Mindell) might be useful to folks in the movement. After our teleconference, the activists encouraged me to write this.

First off, OWS is surrounded by a host of critics, from long-time social change organizers to mainstream media. (Much of the media criticism has been debriefed, so I’m focusing on internal criticisms I have heard.)

We can learn from critics in at least two ways. They can help us improve by pointing out what we genuinely need to change. Paradoxically, they may be criticizing us for something we actually need to do more congruently. Seen from this angle, critics may be highlighting strengths we don’t yet know we have.

Take one criticism: The General Assemblies lead to a kind of individualism of people wanting to be heard and contribute, unaware of the impact on the thousand people listening. In one recent GA, a small group of frustrated men hijacked the meeting, cursing and physically threatening the entire assembly. Even in less dramatic situations, most GA’s are filled with judgment, fracturing statements, and individuals repeating each other just so they can get themselves heard.

From one point of view, the criticism is valid. Yes, Western individualism can be very problematic and it is always a good time to learn to become communitarian. But perhaps there is also something beautiful about this individualism. People have the sense that they can finally speak up about the economy, that their voice is important, that they do not have to shut up and listen to talking heads who supposedly know better.

It can be useful to think about this in terms of roles. (Just as an actor plays many different roles, we all play different roles in our lives, sometimes without awareness.) Individuals wanting to be heard at a General Assembly might be in the role of someone who wants attention. “Pay attention to me! I have something to say!” For years our “democratic” system has ignored these voices. They have been excluded by money, a political system that merely offers citizens a chance to vote, and a financial system bent on inequality. But now this role is finding a public voice.

Recent Comments