You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Mental Health’ category.

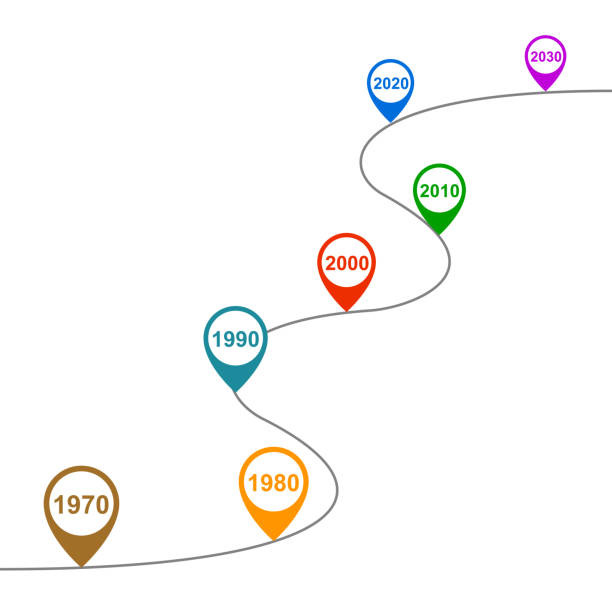

We’re almost four years into the 20s and the sooner we bring back the concept of decades the better. Decades give people, especially young people, a temporal identity and a grounding in history. Decades emphasize the importance of now, but also connect us to the past in a way that doesn’t alienate us from our elders or youths in the way the concept of “generations” does automatically. Decades are a key element of narrative storytelling, encourage critical thinking through comparing/contrasting eras, and make it easier to discuss the future. In sum, decades benefit mental health, social inclusion and connection, movement building, and resistance to the aimless void of late capitalism. Our ability to exercise historical agency and preserve historical memory may depend on us reviving this concept.

If you’re 35 or older, you remember the 60s, 70s, 80s, and 90s as regular talking points. Both in the historical sense of “what was the spirit of the 60s?” and in the future-focused sense of “this will be THE trend of the 90s.” The concept of decades permeated regular conversation, tying people together and rooting them in a temporal home, whether you were talking about music, sports, film, fashion, politics, games, or literally anything. It made it natural and popular to compare eras of things, which is a basic building block of both historical study as well as critical thinking itself. It also helped people form an identity, in the sense of “I’m a child of the 70s” – one shorthand reference point that contains a vast easily-recalled cultural context filled with people, events, products, art, styles, and social struggles. It was a source of pride to be associated with a decade.

When Y2K hit, the computers were just fine. Better than ever, in fact. But we weren’t, because we suddenly lost a very powerful tool for understanding our social environment. Without the concept of decades, we wandered into an amorphous fog without beginning or end, where we became easy-pickings for a consumer capitalism that thrives by developing isolated, disoriented worker-spectators. When ignorant of our past and uninterested in our future, we rarely make trouble for the ruling class.

At first, some people resisted the change. They coined names for the decade-to-be, but none caught on. They sounded forced, so they were relegated to the realm of jokes (Try to have a serious conversation about “the noughties”). Nothing stepped in to bridge the chasm.

It wasn’t a huge problem at first, because the 90s were such a recent frame of reference, so we could keep the concept of decades alive by just filing the present under “post-90s” or “this decade.” All the conversations we were accustomed to, where we compared trends in pants, or hair, or anarchist politics, kept rolling for a while, they just had this weird stand-in where you’d have to compare previous decades to the vague concept of “now.” As in, “you guys had VCRs in the 80s, but now we have the far-superior technology of DVD players, which will remain popular forever.”

Ten years passed. A new decade was scheduled to be starting, but no one took notice. The concept of decades wasn’t revived. Instead, it faded into oblivion. Maybe we were too buried under the infinite scroll of social media, our heads down, absorbed by our smartphones, or too obsessed by the latest streaming content, that we lost the ability to form long-range narratives. Our shared experience of the era itself began to fracture, as our attention scattered into increasingly fragmented niches of the spectacle, which concealed the fact that we were largely all doing the same thing at the same time. Or maybe we were so emotionally beaten down by the seemingly endless “War on Terror” and apocalyptic ecological catastrophe that we simply didn’t have the energy to think of ourselves as historical agents, and therefore couldn’t be bothered with putting a name on the era we were living through, even though “the teens” was an obvious and pleasant choice.

It’s not as if there weren’t massive and historically-important movements for social change happening in that decade. From the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street to Black Lives Matter to MeToo to Transgender visibility, millions of people were organizing, shifting social norms, and becoming empowered to radically improve society in ways perhaps more profound than we know. But compared to movements of the 60s, 70s, 80s, or 90s, these new movements are unusually obscured, and perhaps in danger of being overlooked.

Organizers of these world-changing efforts – people like Alicia Garza and Marisa Holmes – should be recognized and remembered for their actions. Even more importantly, our understanding of how that decade’s movements arose, why they were so effective, and also what their shortcomings were, should be the topic of regular conversation so that we may improve upon them in the future. Yet, it’s nearly impossible to have a productive, civil version of such a discussion on social media, and it may be nearly impossible for a social movement in this day and age to outlast the ephemeral confines of a hashtag.

This is not to suggest that these movements will be forgotten, or to downplay the excellent work of the chroniclers of these efforts, who have produced worthwhile books, documentaries, and other media that actively preserve this historical memory. Instead, I suggest it is unfair to those culture-defining social movements that we can’t immediately recall their powerful messages, images, and actors through a universally-agreed-upon phrase like “the teens” in the same way that “the 60s” immediately conjures such thoughts of the Civil Rights Movement or the anti-Vietnam War movement.

By the way, don’t give me this crap about “generations.” The Civil Rights Movement/Black Freedom Struggle was driven forward by people of all ages, from elders like A. Philip Randolph to middle-aged people like Ella Baker, to children like those who walked out of school to pack the Birmingham jails. As far as I’m aware, the fear-mongering associated with “rebellious youth” has always existed. For sure it existed in the 60s, when the mass media did their best to demonize the anti-authoritarian, hopelessly “feminized” “Baby Boomers”, effectively blaming young people for everything wrong with the world. We’ve come full circle today, blaming those same people, who are now old, for the exact opposite reasons.

“Generations” are a fake conceptual tool used to divide people. Since 2000, as the concept of decades has fallen away, in part it has been superseded by the nefarious concepts of “Millennials” and “Gen. Z.” These are identities which are inherently exclusive, and usually they are invoked for purely negative characterizations. Eventually, “Gen. Z” will get the same scorn that “Boomers” do now, and it will be just as baseless.

In contrast, decades are inherently inclusive. Everyone who was alive in the 90s can reminisce about what that decade was like for them. Even if our experiences were vastly different, we can find common ground through cultural touchstones like The Simpsons or Tupac. That kind of conversation is not just idle nostalgia. It is a collective remembering that allows us to form social bonds with neighbors, co-workers, and fellow activists, to each of whom the 90s is a small building block in their own identity-formation.

If you read comments on Youtube under videos of old music or TV shows (and I’m not recommending you do), you’ll regularly see people lamenting that we no longer live in the [insert decade here]. Some of those commenters are old and feeling nostalgic for the loss of their youth. That’s normal. But some of those commenters are young. They will often mention that they “just turned 16” (or another age of fragile identity-formation). And yet, here they are, wandering the interwebs, watching videos that were produced before they were born and wishing they could time-travel back to the 20th century.

Meanwhile, the 21st century is nearly a quarter complete, and its music and TV shows have been equally valuable, if not more so. But without the decades providing an automatic frame of reference for great artistic works, we struggle to recall exactly when they were released, or how they related to concurrent events in society or technology, or even our own lives. Without decades, people don’t know how to talk to each other about their own time period. And so they don’t. They just slowly forget, as everything is enveloped in a nebulous, meaningless haze.

What stories are children of this century learning about their own time, and where they fit in? What can they be proud of? What can they look forward to?

There’s a bunch of things we could do for a better future for all. Redistributing the wealth of the top 1%. Replacing the private automobile with free public transit. Dismantling the prison-industrial complex in favor of systems of transformative justice and accountability. Planting a billion trees. Those will take a lot of hard work and a long time.

One thing that would take very little effort, would bring us into connection with those around us of all ages, would help us cherish the present and look forward to the future, would empower us to find meaning and feel better, is to reintroduce the concept of decades. We can start now, by acknowledging publicly, and habitually, that we live in the 20s.*

* I mean no disrespect to the decade of the 1920s, a fine decade to study and discuss. But of the decades called “the 20s”, the current decade is far more relevant to everyone living today and for the rest of the 21st century. I don’t know at what point people stopped referring to the 1820s as “the 20s,” but surely it was before 1923.

Johann Hari’s new book “Lost Connections: Uncovering the Real Causes of Depression – and the Unexpected Solutions” provides new, compelling evidence to support the argument from “We Are All Very Anxious” by the Institute for Precarious Consciousness. The argument is that most of us are deeply unhappy, and this unhappiness is a completely rational response to the unhappy conditions of our lives that capitalism has produced.

Specifically, Hari points out how the routine of work under capitalism is making us miserable: “There is strong evidence that human beings need to feel their lives are meaningful – that they are doing something with purpose that makes a difference. It’s a natural psychological need. But between 2011 and 2012, the polling company Gallup conducted the most detailed study ever carried out of how people feel about the thing we spend most of our waking lives doing – our paid work. They found that 13% of people say they are “engaged” in their work – they find it meaningful and look forward to it. Some 63% say they are “not engaged”, which is defined as “sleepwalking through their workday”. And 24% are “actively disengaged”: they hate it.”

Even the United Nations has concluded that “We need to move from ‘focusing on ‘chemical imbalances’’ to focusing more on ‘power imbalances'”. So if we want to be happy, we also need to democratize the economy and give people the power to determine how they want to spend their time and what kinds of work they would actually enjoy doing. [alex]

Is Everything You Think You Know About Depression Wrong?

Originally published by The Guardian, January 7, 2018.

In the 1970s, a truth was accidentally discovered about depression – one that was quickly swept aside, because its implications were too inconvenient, and too explosive. American psychiatrists had produced a book that would lay out, in detail, all the symptoms of different mental illnesses, so they could be identified and treated in the same way across the United States. It was called the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. In the latest edition, they laid out nine symptoms that a patient has to show to be diagnosed with depression – like, for example, decreased interest in pleasure or persistent low mood. For a doctor to conclude you were depressed, you had to show five of these symptoms over several weeks.

The manual was sent out to doctors across the US and they began to use it to diagnose people. However, after a while they came back to the authors and pointed out something that was bothering them. If they followed this guide, they had to diagnose every grieving person who came to them as depressed and start giving them medical treatment. If you lose someone, it turns out that these symptoms will come to you automatically. So, the doctors wanted to know, are we supposed to start drugging all the bereaved people in America?

The authors conferred, and they decided that there would be a special clause added to the list of symptoms of depression. None of this applies, they said, if you have lost somebody you love in the past year. In that situation, all these symptoms are natural, and not a disorder. It was called “the grief exception”, and it seemed to resolve the problem.

Then, as the years and decades passed, doctors on the front line started to come back with another question. All over the world, they were being encouraged to tell patients that depression is, in fact, just the result of a spontaneous chemical imbalance in your brain – it is produced by low serotonin, or a natural lack of some other chemical. It’s not caused by your life – it’s caused by your broken brain. Some of the doctors began to ask how this fitted with the grief exception. If you agree that the symptoms of depression are a logical and understandable response to one set of life circumstances – losing a loved one – might they not be an understandable response to other situations? What about if you lose your job? What if you are stuck in a job that you hate for the next 40 years? What about if you are alone and friendless?

The grief exception seemed to have blasted a hole in the claim that the causes of depression are sealed away in your skull. It suggested that there are causes out here, in the world, and they needed to be investigated and solved there. This was a debate that mainstream psychiatry (with some exceptions) did not want to have. So, they responded in a simple way – by whittling away the grief exception. With each new edition of the manual they reduced the period of grief that you were allowed before being labelled mentally ill – down to a few months and then, finally, to nothing at all. Now, if your baby dies at 10am, your doctor can diagnose you with a mental illness at 10.01am and start drugging you straight away.

Today I’m happy to repost a highly thought-provoking article called “We Are All Very Anxious.” The genius of the piece is that it centers the emotional reality that most of us experience while living under the capitalist system, and attempts to catalogue this emotional reality historically. Of course, what misery, boredom, and anxiety have in common is that they are all forms of powerlessness, because ultimately like any system of power, capitalism rules through convincing the vast majority of its subjects that there is no possible way to overthrow it. It’s therefore important how this article highlights the emotionally liberating content of social movements, and questions our strategies for emotionally connecting with the anxious public.

How do we create spaces and actions where people can most past fear and helplessness and feel genuine hope for a radically different future?

The discussion of the emotional “affects” of capitalism also brings to thinking about care. All living beings need to be cared for – physically, emotionally and sexually. Humans, like other creatures, instinctively care for one another. Therefore any power structure rules by threatening this mutual care and offering access to care only to loyal subjects who work for the system. Patriarchy, of course, structures this rewards and punishment system according to the gender binary, and designates women as the primary carers. How are we told to demonstrate loyalty to the gender system, and what care are we told to expect for such loyalty?

Capitalism has re-structured patriarchy in many ways, one of which has been to monetize care. Those with money are guaranteed to be cared for, while those without face the possibility of isolation and invisibility. Perhaps this is what our anxiety is rooted in – the fear of ending up alone and forgotten if capitalism leaves no room for us (as individuals) to earn a decent living. Could this be one way we imagine building a revolutionary movement in the 21st century – grounded in the universal need of human beings to access care?

[alex]

We Are All Very Anxious: Six Theses on Anxiety and Why It is Effectively Preventing Militancy, and One Possible Strategy for Overcoming It 1

by the Institute for Precarious Consciousness

Republished from Plan C

1: Each phase of capitalism has its own dominant reactive affect. 2

Each phase of capitalism has a particular affect which holds it together. This is not a static situation. The prevalence of a particular dominant affect 3 is sustainable only until strategies of resistance able to break down this particular affect and /or its social sources are formulated. Hence, capitalism constantly comes into crisis and recomposes around newly dominant affects.

Each phase of capitalism has a particular affect which holds it together. This is not a static situation. The prevalence of a particular dominant affect 3 is sustainable only until strategies of resistance able to break down this particular affect and /or its social sources are formulated. Hence, capitalism constantly comes into crisis and recomposes around newly dominant affects.

One aspect of every phase’s dominant affect is that it is a public secret, something that everyone knows, but nobody admits, or talks about. As long as the dominant affect is a public secret, it remains effective, and strategies against it will not emerge.

Public secrets are typically personalised. The problem is only visible at an individual, psychological level; the social causes of the problem are concealed. Each phase blames the system’s victims for the suffering that the system causes. And it portrays a fundamental part of its functional logic as a contingent and localised problem.

In the modern era (until the post-war settlement), the dominant affect was misery. In the nineteenth century, the dominant narrative was that capitalism leads to general enrichment. The public secret of this narrative was the misery of the working class. The exposure of this misery was carried out by revolutionaries. The first wave of modern social movements in the nineteenth century was a machine for fighting misery. Tactics such as strikes, wage struggles, political organisation, mutual aid, co-operatives and strike funds were effective ways to defeat the power of misery by ensuring a certain social minimum. Some of these strategies still work when fighting misery.

When misery stopped working as a control strategy, capitalism switched to boredom. In the mid twentieth century, the dominant public narrative was that the standard of living – which widened access to consumption, healthcare and education – was rising. Everyone in the rich countries was happy, and the poor countries were on their way to development. The public secret was that everyone was bored. This was an effect of the Fordist system which was prevalent until the 1980s – a system based on full-time jobs for life, guaranteed welfare, mass consumerism, mass culture, and the co-optation of the labour movement which had been built to fight misery. Job security and welfare provision reduced anxiety and misery, but jobs were boring, made up of simple, repetitive tasks. Mid-century capitalism gave everything needed for survival, but no opportunities for life; it was a system based on force-feeding survival to saturation point.

Of course, not all workers under Fordism actually had stable jobs or security – but this was the core model of work, around which the larger system was arranged. There were really three deals in this phase, with the B-worker deal – boredom for security – being the most exemplary of the Fordism-boredom conjuncture. Today, the B-worker deal has largely been eliminated, leaving a gulf between the A- and C-workers (the consumer society insiders, and the autonomy and insecurity of the most marginal).

2: Contemporary resistance is born of the 1960s wave, in response to the dominant affect of boredom.

If each stage of the dominant system has a dominant affect, then each stage of resistance needs strategies to defeat or dissolve this affect. If the first wave of social movements were a machine for fighting misery, the second wave (of the 1960s-70s, or more broadly (and thinly) 1960s-90s) were a machine for fighting boredom. This is the wave of which our own movements were born, which continues to inflect most of our theories and practices. Read the rest of this entry »

“Invisible and unspeakable, without a meaningful lexicon, is the world of care. No human could survive or thrive without touch, affection, nurturing, attention, compassion, validation, or empathy–yet the need for these acts of care (which are often gendered as feminine, no matter who provides them) has been subsumed into necessary invisibility by a system that depends on depriving us of the means to tend to our own lives.”

“Alienation and Intimacy”

by Corina Dross

Originally posted on Revolt, She Said.

Intimacy is often considered outside the realm of political discourse; politics is what we do out there, not what happens in our homes, our friendships, and our romances. We know this is false, but that knowledge itself doesn’t transform our lives.

We still carry shame and fear about our private needs and desires–and we look to our communities for clues about the appropriate ways to get these needs met. So when we mirror for each other the same policing and oppression we’ve learned from the larger culture, we’re failing to demand a better world for ourselves and the people we love.

The enterprise of radical relationships is to create a language that we haven’t yet learned, that can subvert the language we’ve been given, as we struggle to analyze how the alienation that permeates our world specifically functions in the details of our intimate lives. It’s important that this enterprise be public and collective, to avoid the trap of buying into the self-help book mentality–which advises us to analyze our own deepest fears and worst habits alone or with a therapist, or with a partner or best friend–but as an individual project, without agitating for the world to better meet our collective needs.

And our own worst habits are not merely ours; most likely, they arise in response to larger systems of oppression, which we all face, and which we internalize. There are multiple intersections of oppression in our lives, but let’s focus here on capitalist processes of alienation. If we look at some specific ways capitalism creates suffering–and makes this suffering appear normal and invisible–we may see parallels in our intimate lives and begin to formulate forms of resistance.

There are many cultural side-effects of the capitalist project, worth discussing in future conversations, but for now let’s start with the idea of artificial scarcity.

If we agree that capitalism shapes our world through processes that consolidate wealth, power, and resources amongst very few–creating scarcity and need for the rest of us, robbing us of time to pursue our own deepest desires and interests, time with friends and loved ones, access to healthy food and housing, access to medical care, and a thousand other necessary things, we can imagine how much pressure there is on our intimate relationships, which are supposedly outside of the public sphere, to be sites of abundance. It’s somewhat fantastical that we could expect one person (or several, depending on how we arrange our love lives) to make up for all that lack. But popular narratives reinforce this: that love will fix all our problems; that a long-lasting romantic partnership should fill all that is empty in us; that we must give to our lovers all that the world can’t.

Republished by Energy Bulletin, Countercurrents and OpEdNews.

The following exchange between Michael Carriere and Alex Knight occurred via email, July 2010. Alex Knight was questioned about the End of Capitalism Theory, which states that the global capitalist system is breaking down due to ecological and social limits to growth and that a paradigm shift toward a non-capitalist future is underway.

This is the final part of a four-part interview. Scroll to the bottom for links to the other sections.

Part 3. Life After Capitalism

MC: Moving forward, how would you ideally envision a post-capitalist world? And if capitalism manages to survive (as it has in the past), is there still room for real change?

AK: First let me repeat that even if my theory is right that capitalism is breaking down, it doesn’t suggest that we’ll automatically find ourselves living in a utopia soon. This crisis is an opportunity for us progressives but it is also an opportunity for right-wing forces. If the right seizes the initiative, I fear they could give rise to neo-fascism – a system in which freedoms are enclosed and violated for the purpose of restoring a mythical idea of national glory.

I think this threat is especially credible here in the United States, where in recent years we’ve seen the USA PATRIOT Act, the Supreme Court’s decision that corporations are “persons,” and the stripping of constitutional rights from those labeled “terrorists,” “enemy combatants”, as well as “illegals.” Arizona’s attempt to institute a racial profiling law and turn every police officer into an immigration official may be the face of fascism in America today. Angry whites joining together with the repressive forces of the state to terrorize a marginalized community, Latino immigrants. While we have a black president now, white supremacist sentiment remains widespread in this country, and doesn’t appear to be going away anytime soon. So as we struggle for a better world we may also have to contend with increasing authoritarianism.

I should also state up front that I have no interest in “writing recipes for the cooks of the future.” I can’t prescribe the ideal post-capitalist world and I wouldn’t try. People will create solutions to the crises they face according to what makes most sense in their circumstances. In fact they’re already doing this. Yet, I would like to see your question addressed towards the public at large, and discussed in schools, workplaces, and communities. If we have an open conversation about what a better world would look like, this is where the best solutions will come from. Plus, the practice of imagination will give people a stronger investment in wanting the future to turn out better. So I’ll put forward some of my ideas for life beyond capitalism, in the hope that it spurs others to articulate their visions and initiate conversation on the world we want.

My personal vision has been shaped by my outrage over the two fundamental crises that capitalism has perpetrated: the ecological crisis and the social crisis. I see capitalism as a system of abuse. The system grows by exploiting people and the planet as means to extract profit, and by refusing to be responsible for the ecological and social trauma caused by its abuse. Therefore I believe any real solutions to our problems must be aligned to both ecological justice and social justice. If we privilege one over the other, we will only cause more harm. The planet must be healed, and our communities must be healed as well. I would propose these two goals as a starting point to the discussion.

How do we heal? What does healing look like? Let me expand from there.

Five Guideposts to a New World

I mentioned in response to the first question that I view freedom, democracy, justice, sustainability and love as guideposts that point towards a new world. This follows from what I call a common sense radical approach, because it is not about pulling vision for the future from some ideological playbook or dogma, but from lived experience. Rather than taking pre-formed ideas and trying to make reality fit that conceptual blueprint, ideas should spring from what makes sense on the ground. The five guideposts come from our common values. It doesn’t take an expert to understand them or put them into practice.

In the first section I described how freedom at its core is about self-determination. I said that defined this way it presents a radical challenge to capitalist society because it highlights the lack of power we have under capitalism. We do not have self-determination, and we cannot as long as huge corporations and corrupt politicians control our destinies.

I’ll add that access to land is fundamental to a meaningful definition of freedom. The group Take Back the Land has highlighted this through their work to move homeless and foreclosed families directly into vacant homes in Miami. Everyone needs access to land for the basic security of housing, but also for the ability to feed themselves. Without “food sovereignty,” or the power to provide for one’s own family, community or nation with healthy, culturally and ecologically appropriate food, freedom cannot exist. The best way to ensure that communities have food sovereignty is to ensure they have access to land.

Similarly, a deeper interpretation of democracy would emphasize participation by an individual or community in the decisions that affect them. For this definition I follow in the footsteps of Ella Baker, the mighty civil rights organizer who championed the idea of participatory democracy. With a lifelong focus on empowering ordinary people to solve their own problems, Ella Baker is known for saying “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.” This was the philosophy of the black students who sat-in at lunch counters in the South to win their right to public accommodations. They didn’t wait for the law to change, or for adults to tell them to do it. The students recognized that society was wrong, and practiced non-violent civil disobedience , becoming empowered by their actions. Then with Ms. Baker’s support they formed the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and organized poor blacks in Mississippi to demand their right to vote, passing on the torch of empowerment.

We need to be empowered to manage our own affairs on a large scale. In a participatory democracy, “we, the people” would run the show, not representatives who depend on corporate funding to get elected. “By the people, for the people, of the people” are great words. What if we actually put those words into action in the government, the economy, the media, and all the institutions that affect our lives? Institutions should obey the will of the people, rather than the people obeying the will of institutions. It can happen, but only through organization and active participation of the people as a whole. We must empower ourselves, not wait for someone else to do it. Read the rest of this entry »

An excellent talk on the relation between mental health and capitalism/neoliberalism. This is worth watching all the way through if you can. Dr. Stephen Bezruchka discusses the pharmaceutical/psychiatric industry and the spiraling rates of anti-depressants and other drugs given out to adults and children. This medicating of America doesn’t seem to be curbing mental illness or mental disorders, which are more prevalent in the US today than ever before, or in any other countries.

He suggests a more “caring and sharing” society, focused especially on better childhood development and reducing the gap between rich and poor, would do much to help us heal our over-stressed and depressed nation. This is a great line of thought, as understanding psychological disorder within the context of political decision-making allows us to imagine strategies to overcome it. Human-made problems have human solutions.

Recent Comments