You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Winning’ category.

Republished by Energy Bulletin, Countercurrents and OpEdNews.

The following exchange between Michael Carriere and Alex Knight occurred via email, July 2010. Alex Knight was questioned about the End of Capitalism Theory, which states that the global capitalist system is breaking down due to ecological and social limits to growth and that a paradigm shift toward a non-capitalist future is underway.

This is the final part of a four-part interview. Scroll to the bottom for links to the other sections.

Part 3. Life After Capitalism

MC: Moving forward, how would you ideally envision a post-capitalist world? And if capitalism manages to survive (as it has in the past), is there still room for real change?

AK: First let me repeat that even if my theory is right that capitalism is breaking down, it doesn’t suggest that we’ll automatically find ourselves living in a utopia soon. This crisis is an opportunity for us progressives but it is also an opportunity for right-wing forces. If the right seizes the initiative, I fear they could give rise to neo-fascism – a system in which freedoms are enclosed and violated for the purpose of restoring a mythical idea of national glory.

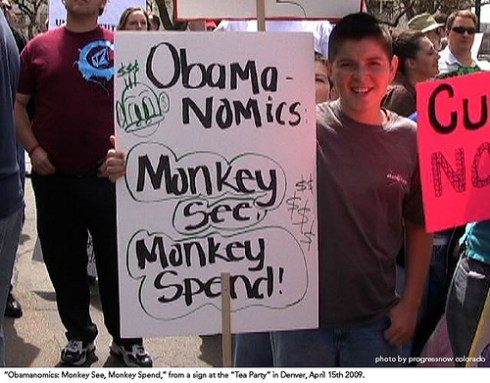

I think this threat is especially credible here in the United States, where in recent years we’ve seen the USA PATRIOT Act, the Supreme Court’s decision that corporations are “persons,” and the stripping of constitutional rights from those labeled “terrorists,” “enemy combatants”, as well as “illegals.” Arizona’s attempt to institute a racial profiling law and turn every police officer into an immigration official may be the face of fascism in America today. Angry whites joining together with the repressive forces of the state to terrorize a marginalized community, Latino immigrants. While we have a black president now, white supremacist sentiment remains widespread in this country, and doesn’t appear to be going away anytime soon. So as we struggle for a better world we may also have to contend with increasing authoritarianism.

I should also state up front that I have no interest in “writing recipes for the cooks of the future.” I can’t prescribe the ideal post-capitalist world and I wouldn’t try. People will create solutions to the crises they face according to what makes most sense in their circumstances. In fact they’re already doing this. Yet, I would like to see your question addressed towards the public at large, and discussed in schools, workplaces, and communities. If we have an open conversation about what a better world would look like, this is where the best solutions will come from. Plus, the practice of imagination will give people a stronger investment in wanting the future to turn out better. So I’ll put forward some of my ideas for life beyond capitalism, in the hope that it spurs others to articulate their visions and initiate conversation on the world we want.

My personal vision has been shaped by my outrage over the two fundamental crises that capitalism has perpetrated: the ecological crisis and the social crisis. I see capitalism as a system of abuse. The system grows by exploiting people and the planet as means to extract profit, and by refusing to be responsible for the ecological and social trauma caused by its abuse. Therefore I believe any real solutions to our problems must be aligned to both ecological justice and social justice. If we privilege one over the other, we will only cause more harm. The planet must be healed, and our communities must be healed as well. I would propose these two goals as a starting point to the discussion.

How do we heal? What does healing look like? Let me expand from there.

Five Guideposts to a New World

I mentioned in response to the first question that I view freedom, democracy, justice, sustainability and love as guideposts that point towards a new world. This follows from what I call a common sense radical approach, because it is not about pulling vision for the future from some ideological playbook or dogma, but from lived experience. Rather than taking pre-formed ideas and trying to make reality fit that conceptual blueprint, ideas should spring from what makes sense on the ground. The five guideposts come from our common values. It doesn’t take an expert to understand them or put them into practice.

In the first section I described how freedom at its core is about self-determination. I said that defined this way it presents a radical challenge to capitalist society because it highlights the lack of power we have under capitalism. We do not have self-determination, and we cannot as long as huge corporations and corrupt politicians control our destinies.

I’ll add that access to land is fundamental to a meaningful definition of freedom. The group Take Back the Land has highlighted this through their work to move homeless and foreclosed families directly into vacant homes in Miami. Everyone needs access to land for the basic security of housing, but also for the ability to feed themselves. Without “food sovereignty,” or the power to provide for one’s own family, community or nation with healthy, culturally and ecologically appropriate food, freedom cannot exist. The best way to ensure that communities have food sovereignty is to ensure they have access to land.

Similarly, a deeper interpretation of democracy would emphasize participation by an individual or community in the decisions that affect them. For this definition I follow in the footsteps of Ella Baker, the mighty civil rights organizer who championed the idea of participatory democracy. With a lifelong focus on empowering ordinary people to solve their own problems, Ella Baker is known for saying “Strong people don’t need strong leaders.” This was the philosophy of the black students who sat-in at lunch counters in the South to win their right to public accommodations. They didn’t wait for the law to change, or for adults to tell them to do it. The students recognized that society was wrong, and practiced non-violent civil disobedience , becoming empowered by their actions. Then with Ms. Baker’s support they formed the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and organized poor blacks in Mississippi to demand their right to vote, passing on the torch of empowerment.

We need to be empowered to manage our own affairs on a large scale. In a participatory democracy, “we, the people” would run the show, not representatives who depend on corporate funding to get elected. “By the people, for the people, of the people” are great words. What if we actually put those words into action in the government, the economy, the media, and all the institutions that affect our lives? Institutions should obey the will of the people, rather than the people obeying the will of institutions. It can happen, but only through organization and active participation of the people as a whole. We must empower ourselves, not wait for someone else to do it. Read the rest of this entry »

Republished by Energy Bulletin, OpEdNews, and Countercurrents, and translated into Turkish for Hafif.org.

The following exchange between Michael Carriere and Alex Knight occurred via email, July 2010. Alex Knight was questioned about the End of Capitalism Theory, which states that the global capitalist system is breaking down due to ecological and social limits to growth and that a paradigm shift toward a non-capitalist future is underway.

This is the third part of a four-part interview. This part is a continuation of Alex’s response to the second question. Click here for Part 2A. Scroll to the bottom for links to the other sections.

Part 2B. Social Limits and the Crisis

MC: Capitalism has faced many moments of crisis over time. Is there something different about the present crisis? What makes the end of capitalism a possibility now?

AK: As I described in the last section, the current crisis can be understood as resulting from a massive collision between capitalism’s relentless need for growth and the world’s limits in capacity to sustain that growth. These limits to growth are both ecological and social. In this section I’ll discuss the concept of social limits to growth.

The Extraordinary Power of Social Movements

Social limits to growth function alongside the ecological limits but are drawn from a different source. By social limits we mean the inability, or unwillingness, of human communities, and humankind as a whole, to support the expansion of capitalism. This broadly includes all forms of resistance to capitalism, a resistance that has arguably been increasing around the world through innumerable forms of alternative lifestyles, refusal to cooperate, protest, and outright rebellion.

As a disclaimer it’s important to recognize that not all resistance is progressive. There are right-wing, fundamentalist, and undemocratic forces that also resist capitalism, for example the Taliban, or North Korea. These are not our allies. They do not share progressive values, we cannot condone their attacks on women, or on freedom more generally, and I don’t see anything to be gained by working with them. However it is important to recognize how these forces are aligned against capitalism and U.S. imperialism, in addition to being aware of the danger they present to our own hopes and dreams.

Progressive resistance, on the other hand, has always taken its strength from grassroots social movements. Silvia Federici writes about the immense and varied peasant movements in medieval Europe that fought for religious and sexual freedom, challenging both feudal lords and emerging capitalist elites. I like to think of these rebels as my European ancestors – they were just commoners but they rose up to fight for a better world. This is the nature of social movements. Ordinary folks, daring to pursue their deepest aspirations, interests and dreams, join together with others who share those desires, and thereby create something extraordinary. The magic exists in the joining-together. Isolated individuals lack the power to accomplish what a group can achieve.

We can appreciate this extraordinary power if we look at how social movements have transformed our lives. A century ago, millions of American workers joined the labor movement and won the 8-hour day, Social Security, and workplace safety. Regular folks carried forward the Civil Rights Movement and broke Southern segregation. The feminist and LGBT movements have transformed the way gender and sexuality are viewed all over the world. It’s hard to overstate how dramatically these and other social movements have improved society. While capitalism has invented ways to co-opt social movements and redirect them into outlets that do not challenge the system on a deep level (like the “non-profit industrial complex”), movements have remained alive and vibrant by empowering people to reach towards a different world.

Have social movements limited capitalist oppression recently? To answer this we need to learn the story of the Global Justice Movement.

Demonstrators tear down a section of security fence in the Mexican resort city of Cancun to confront the World Trade Organization’s Fifth Ministerial summit on Sept. 10, 2003.

The Global Justice Movement

David Graeber, anarchist anthropologist, wrote a remarkable essay called “The Shock of Victory” in which he looks at this movement that suddenly flared up at the turn of the millennium and seemed to disappear just as quickly. Although most Americans may not remember the Global Justice Movement, and those who participated in it may feel demoralized by the fact that capitalism still exists, Graeber points out that many of the movement’s ambitious goals were accomplished. Read the rest of this entry »

Engaging the Crisis: Organizing Against Budget Cuts and Community Power in Philadelphia

by Kristin Campbell

Reposted from Organizing Upgrade, March 1, 2010

Organizing Upgrade is honored to offer a preview of this insightful reflection on organizing – Engaging the Crisis: Organizing Against Budget Cuts and Building Community Power in Philadelphia – which will appear in Left Turn magazine #36 (April/May 2010). You can subscribe to Left Turn online at www.leftturn.org or become a monthly sustainer at www.leftturn.org/donate.

On November 6, 2008, just days after Philadelphians poured onto the streets to celebrate the Phillies winning the World Series championship and Barack Obama the US presidency, Mayor Michael Nutter announced a drastic plan to deal with the cities $108 million budget gap. Severe budget cuts were announced, including the closure of 11 public libraries, 62 public swimming pools, 3 public ice skating rinks, and several fire engines. Nutter also stated that 220 city workers would be laid off and that 600 unfilled positions would be eliminated entirely, amounting to the loss of nearly 1,000 precious city jobs. In classic neo-liberal style, the public sector was to sacrifice, while taxpayer money would bail out the private banking institutions.

City in crisis

Well before the economic crises of 2008, a decades-long process of economic restructuring and deindustrialization had left Philadelphia, with a population just over 1.4 million, an incredibly under-resourced city. Philadelphia has the highest poverty rate out of the ten largest cities in the US, an eleven percent unemployment rate and a high-school dropout rate that hovers dangerously around 50 percent.

The proposed budget cuts sparked waves of popular outrage especially concerning the closure of the libraries, many of which are located in low-income communities of color and serve as bedrock institutions for many basic resources. Eleanor Childs, a principal of a school that heavily relies on West Philadelphia’s Durham library, and later a member of the Coalition to Save the Libraries, recalls “a groundswell of concern about the closing of the libraries… people rose up. We had our pitchforks. We were ready to fight to keep our libraries open.”

Nutter’s administration set up eight townhall meetings across Philadelphia, designed to calm the citywide uproar. Thousands of people filled the townhall meetings poised to question how such drastic decisions were made without any public input. Under the banner “Tight Times, Tough Choices,” Mayor Nutter and senior city officials attempted to explain the necessity of such deep service cuts. They explained that the impact of the economic crisis on the city had only become apparent in recent weeks, and because the city could not raise significant revenue to offset its financial loses in the timeframe that was needed, rapid cuts were mandatory and effective January 1, 2009.

Community response

In the following days and weeks, Philadelphians quickly mobilized against the decision that their public services and city workers pay for the fallout of a economic system that had already left so many of them struggling. Neighborhood leaders organized impromptu rallies at the eleven branch libraries. Along with organizing people to turn out at the Mayor’s townhall meetings, these rallies gained media attention on both the nightly news and in the major newspapers, demonstrating widespread opposition to the budget cuts. Sherrie Cohen, member of the Coalition to Save the Libraries and long-time resident of the Ogontz neighborhood of North Philly remembers her neighbors coming together to say, “We are not going to let this library close. It’s not gonna happen. We fought for 36 years for a library in our neighborhood.” Read the rest of this entry »

Wonderful essay by Stephanie Guilloud on the shifting sands of movement strategy in the wake of the high-tide of the Global Justice Movement, which in Seattle articulated a world beyond capitalism that was not controlled by corporate giants and corrupt governments, but built by democratic cooperation of communities all around the world.

The Seattle direct actions shut down the World Trade Organization for a weekend in 1999, because the WTO had been spreading the corporate agenda across the planet, and this began a string of movement victories that shut down the WTO permanently – by delegitimizing the organization and emboldening Global South nations to refuse rich countries’ poverty-spreading deals and abandon its negotiations.

Now, as Global South nations lead the call for justice in Copenhagen and as we gear up for the US Social Forum in Detroit next summer, it’s a great time to look back at the lessons the movement for justice, democracy and sustainability has learned in the past decade. [alex]

From Seattle to Detroit: 10 Lessons for Movement Building on the 10th Anniversary of the WTO Shutdown

From Seattle to Detroit: 10 Lessons for Movement Building on the 10th Anniversary of the WTO Shutdown

By Stephanie Guilloud November 30, 2009 | Reposted from the Indypendent

For five days in 1999, 80,000 people from Seattle and from all over the country stopped the World Trade Organization from meeting. Despite extreme police and state violence, students, organizers, workers, and community members participated in a public uprising using direct actions, marches, rallies, and mass convergences. Longshoremen shut down every port on the West Coast. Global actions of solidarity happened from India to Italy. Trade ministers, heads of state, and corporate hosts were forced to abandon their agenda and declare the Millenium Ministerial a complete failure. We said we would shut it down, and we did.

“The fact is that the Social Forum and Peoples Movement Assembly process actually started in Seattle. The Social Forum took off from the experience of the ‘Battle of Seattle’ when the Brazilian organizing committee formed in 2000 and held the first World Social Forum in 2001. Ten years later, we come back to where this started. What has been accomplished in the last 10 years? How have our social movements developed to build the power towards real social systemic change in the US? How do we map the new forces and what is the power of the social movement assembly?”

– Ruben Solis, Southwest Workers Union, participant in the Seattle shutdown, and one of the founders of the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance

As one of the founders and leaders of the Direct Action Network and a resident of Olympia, Washington, I offer personal and political reflections on the WTO shutdown as a major turning point in my life as an organizer and in our lives working to build movements in the US. As an organizer with the US Social Forum process and a co-lead to develop the People’s Movement Assembly, I carry these lessons with me on a daily basis. I offer these stories with humility and a sense of responsibility. When I refer to “we” in this brief article, I refer to my community of young people in their early twenties, living in Seattle, Olympia, Portland, and the Bay Area, who, with many others, mobilized, organized, and implemented the direct action strategies we had planned for months.

1.) Know your history: Seattle was a turning point

Seattle was a historic turning point in our movements for racial, economic and gender justice for a few reasons. On a global scale, the demonstrations and effective shutdown of the World Trade Organization’s ministerial was historic because of our position and location in the US. Seattle did not mark the beginning of a movement, it marked the beginning of a significant connection between the US and the rest of the world. Global movements had and have been challenging and confronting financial institutions and their systemic effects for decades. The demonstrations – the five days of direct action, the massive and violent state response, and the subsequent alliances – accomplished a few major shifts in historic directions. The demonstrations exposed to the US public the tangible affects of globalization on regular people’s lives. The effectiveness of the actions and stalling of the meetings allowed for delegates from the global South to challenge the policies and procedures of the WTO. And for the first time in history, the decision-making rounds of a global financial institution collapsed.

Seattle also opened a door on a new era for movement in the US. The strengths and weaknesses of our organizing efforts served as a spark for new work, new alliances, new conversations, and a new generational drive. It opened the possibility for a generation of people to understand action, movement, and strategy as effective. It also offered an opportunity to see the strengths of innovation and mass organizing, as well as the weaknesses of underdeveloped leadership and lack of connection to long-term transformative practices.

2.) Claim your victories and evaluate your mistakes. Read the rest of this entry »

Also published by The Rag Blog and OpEdNews.

“We stand at a critical moment in Earth’s history, a time when humanity must choose its future. As the world becomes increasingly interdependent and fragile, the future at once holds great peril and great promise. To move forward we must recognize that in the midst of a magnificent diversity of cultures and life forms we are one human family and one Earth community with a common destiny. We must join together to bring forth a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace. Towards this end, it is imperative that we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations. – The Earth Charter” (pg. 1).

“We stand at a critical moment in Earth’s history, a time when humanity must choose its future. As the world becomes increasingly interdependent and fragile, the future at once holds great peril and great promise. To move forward we must recognize that in the midst of a magnificent diversity of cultures and life forms we are one human family and one Earth community with a common destiny. We must join together to bring forth a sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace. Towards this end, it is imperative that we, the peoples of Earth, declare our responsibility to one another, to the greater community of life, and to future generations. – The Earth Charter” (pg. 1).

David Korten, long-time global justice activist, co-founder of Yes! Magazine, and author of such books as When Corporations Rule the World, lays out the fundamental crossroads facing the world in his 2006 book The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community. In response to global climate change, war, oil scarcity, persistent racism and sexism and many other mounting crises, Korten argues we must recognize these as symptoms of a larger system of Empire, so that we might move in a radically different direction of equality, ecological sustainability, and cooperation, which he terms Earth Community. This is a powerful and important book, which excels in overviewing the big picture of threats facing our ecosphere and our communities at the hands of global capitalism1, and translating this into the simplest and most accessible language so we might all do something about it. It’s pretty much anti-capitalism for the masses. And it has the power to inspire many of us to transform our lives and work towards the transformation of society.

Capitalism and Empire

Of course, Korten has made the strategic decision to avoid pointing the finger at “capitalism” as such in order to speak to an American public which largely still confuses the term as equivalent to “freedom” or “democracy.” In fact the “C” word is rarely mentioned in the book, almost never without some sort of modifier as in “corporate capitalism” or “predatory capitalism”, as if those weren’t already features of the system as a whole. Instead, Korten names “Empire” as the culprit responsible for our global economic and ecological predicament, which is defined as a value-system that promotes the views that “Humans are flawed and dangerous”, “Order by dominator hierarchy”, “Compete or die”, “Masculine dominant”, etc. (32).

Korten explains that Empire, “has been a defining feature of the most powerful and influential human societies for some five thousand years, [and] appropriates much of the productive surplus of society to maintain a system of dominator power and elite competition. Racism, sexism, and classism are endemic features” (25). In this way the anarchist concept of the State is repackaged as a transcendent human tendency, which has more to do with conscious decision-making and maturity level than it does with political power. While this compromise does limit the book’s effectiveness in offering solutions later on, it does speak in a language more familiar to the vast non-politicized majority of Americans, and may have the potential to unify a larger movement for change.

Whatever you want to call the system, the danger it presents to the planet is now clear. Korten spells out the grim statistics: “Fossil fuel use is five times what it was [in 1950], and global use of freshwater has tripled… the [Arctic] polar ice cap has thinned by 46 percent over twenty years… [while we’ve seen] a steady increase over the past five decades in severe weather events such as major hurricanes, floods, and droughts. Globally there were only thirteen severe events in the 1950s. By comparison, seventy-two such events occurred during the first nine years of the 1990s” (59-60). If this destruction continues, it’s uncertain if the Earth will survive.

This ecological damage is considered alongside the social damage of billions living without clean water or adequate food, as well as the immense costs of war and genocide. But Korten understands that the danger is relative to where you stand in the social hierarchy – the system creates extreme poverty for many, and an extreme wealth for a few others. He explains how the system is based on a deep inequality that is growing ever worse, “In the 1990s, per capita income fell in fifty-four of the world’s poorest countries… At the other end of the scale, the number of billionaires worldwide swelled from 274 in 1991 to 691 in 2005” (67). The critical point that these few wealthy elites wield excessive power and influence within the system to stop or slow necessary reform could be made more clearly, but at least the book exposes the existence of this upper class, who are usually quite effective at hiding from public scrutiny and outrage over the suffering they are causing.2

Earth Community – Growing a Revolution

Standing at odds with the bastions of Empire is what David Korten calls “Earth Community,” a “higher-order” value-system promoting the views of, “Cooperate and live,” “Love life”, “Defend the rights of all”, “Gender balanced”, etc. (32). Read the rest of this entry »

Recent Comments