You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Patriarchy’ category.

Also published by The Rag Blog, OpEdNews, Signs of the Times, Interactivist Info Exchange, and Toward Freedom.

Who Were the Witches? – Patriarchal Terror and the Creation of Capitalism

Who Were the Witches? – Patriarchal Terror and the Creation of Capitalism

Alex Knight

November 5, 2009

This Halloween season, there is no book I could recommend more highly than Silvia Federici’s brilliant Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia 2004), which tells the dark saga of the Witch Hunt that consumed Europe for more than 200 years. In uncovering this forgotten history, Federici exposes the origins of capitalism in the heightened oppression of workers (represented by Shakespeare’s character Caliban), and most strikingly, in the brutal subjugation of women. She also brings to light the enormous and colorful European peasant movements that fought against the injustices of their time, connecting their defeat to the imposition of a new patriarchal order that divided male from female workers. Today, as more and more people question the usefulness of a capitalist system that has thrown the world into crisis, Caliban and the Witch stands out as essential reading for unmasking the shocking violence and inequality that capitalism has relied upon from its very creation.

Who Were the Witches?

Parents putting a pointed hat on their young son or daughter before Trick-or-Treating might never pause to wonder this question, seeing witches as just another cartoonish Halloween icon like Frankenstein’s monster or Dracula. But deep within our ritual lies a hidden history that can tell us important truths about our world, as the legacy of past events continues to affect us 500 years later. In this book, Silvia Federici takes us back in time to show how the mysterious figure of the witch is key to understanding the creation of capitalism, the profit-motivated economic system that now reigns over the entire planet.

During the 15th – 17th centuries the fear of witches was ever-present in Europe and Colonial America, so much so that if a woman was accused of witchcraft she could face the cruellest of torture until confession was given, or even be executed based on suspicion alone. There was often no evidence whatsoever. The author recounts, “for more than two centuries, in several European countries, hundreds of thousands of women were tried, tortured, burned alive or hanged, accused of having sold body and soul to the devil and, by magical means, murdered scores of children, sucked their blood, made potions with their flesh, caused the death of their neighbors, destroyed cattle and crops, raised storms, and performed many other abominations” (169).

In other words, just about anything bad that might or might not have happened was blamed on witches during that time. So where did this tidal wave of hysteria come from that took the lives so many poor women, most of whom had almost certainly never flown on broomsticks or stirred eye-of-newt into large black cauldrons?

Caliban underscores that the persecution of witches was not just some error of ignorant peasants, but in fact the deliberate policy of Church and State, the very ruling class of society. To put this in perspective, today witchcraft would be a far-fetched cause for alarm, but the fear of hidden terrorists who could strike at any moment because they “hate our freedom” is widespread. Not surprising, since politicians and the media have been drilling this frightening message into people’s heads for years, even though terrorism is a much less likely cause of death than, say, lack of health care.1 And just as the panic over terrorism has enabled today’s powers-that-be to attempt to remake the Middle East, this book makes the case that the powers-that-were of Medieval Europe exploited or invented the fear of witches to remake European society towards a social paradigm that met their interests.

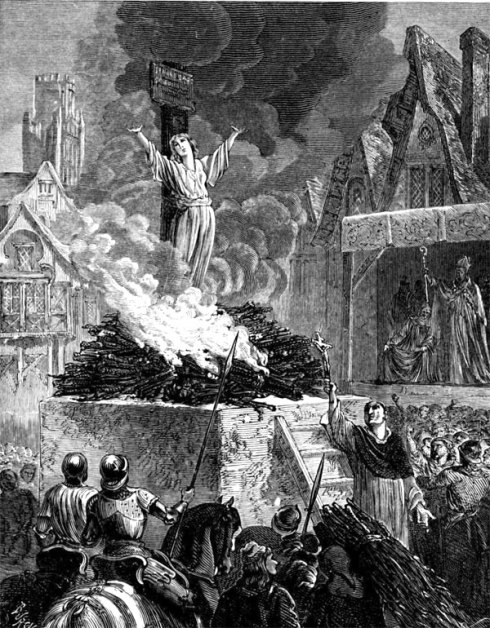

Interestingly, a major component of both of these crusades was the use of so-called “shock and awe” tactics to astound the population with “spectacular displays of force,” which helped to soften up resistance to drastic or unpopular reforms.2 In the case of the Witch Hunt, shock therapy was applied through the witch burnings – spectacles of such stupefying violence that they paralyzed whole villages and regions into accepting fundamental restructuring of medieval society.3 Federici describes a typical witch burning as, “an important public event, which all the members of the community had to attend, including the children of the witches, especially their daughters who, in some cases, would be whipped in front of the stake on which they could see their mother burning alive” (186).

The witch burning was the medieval version of "Shock and Awe"

The book argues that these gruesome executions not only punished “witches” but graphically demonstrated the repercussions for any kind of disobedience to the clergy or nobility. In particular, the witch burnings were meant to terrify women into accepting “a new patriarchal order where women’s bodies, their labor, their sexual and reproductive powers were placed under the control of the state and transformed into economic resources” (170). Read the rest of this entry »

The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy

The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy

by Murray Bookchin

1982 Cheshire Books

Murray Bookchin (R.I.P., 2006) was one of the most important American theorists of the 20th century. He is most known for pioneering and promoting social ecology, which holds that “the very notion of the domination of nature by man stems from the very real domination of human by human.” In other words, the only way to resolve the ecological crisis is to create a free and democratic society.

The Ecology of Freedom is one of Bookchin’s classic works, in which he not only outlines social ecology, but exposes hierarchy, “the cultural, traditional and psychological systems of obedience and command”, from its emergence in pre-‘civilized’ patriarchy all the way to capitalism today. The book explains that hierarchy is exclusively a human phenomena, one which has only existed for a relatively short period of time in humanity’s 2 million year history. For that reason, and also because he finds examples of people resisting and overturning hierarchies ever since their emergence, Bookchin believes we can create a world based on social equality, direct democracy and ecological sustainability.

It seems to me this fundamental hope in human possibility is the most essential contribution of this book. In discussing healthier forms of life than we currently inhabit, Bookchin makes a distinction between “organic societies”, which were pre-literate, hunter-gatherer human communities existing before hierarchy took over, and “ecological society”, which he hopes we will create to bring humanity back into balance with nature, but without losing the intellectual and artistic advances of “civilization” (his quote-marks).

Of ‘organic society’ he says “I use the term to denote a spontaneously formed, noncoercive, and egalitarian society – a ‘natural’ society in the very definite sense that it emerges from innate human needs for association, interdependence, and care.” This, he explains, is where we come from. Not a utopia free of problems, but a real society based on the principle of “unity of diversity,” meaning respect for each member of the community, regardless of sex, age, etc. – an arrangement that is free of domination. Read the rest of this entry »

“American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America”

“American Fascists: The Christian Right and the War on America”

Chris Hedges

2006 Free Press

Are right-wing Christians in America developing a potentially fascist movement that would discard democracy for the sake of security and conservative values? This is answered affirmatively by Chris Hedges, author of War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, in his newest book.

We all know the worst of the evangelical movement, which Hedges calls the “dominionists”: they’re militantly anti-abortion and promote abstinence-only education, they hate queer and trans people, they don’t believe in evolution or environmentalism, they’re racist against immigrants and support US warfare and imperialism, and they can be violent, potentially terroristic. This book explores all of these themes, but it also exposes the frightening strength these people have in our society.

For example, “There are at least 70 million evangelicals in the United States attending more than 240,000 evangelical churches… Polls indicate that about 40 percent of respondents believe the Bible is ‘to be taken literally, word for word.’ .. Almost a third of all respondents say they believe in the Rapture.” Clearly this movement has developed a mass base by hiding behind Christianity.

But are these folks organized? Hedges says yes, quite so. He points to their dominance over the Republican Party, as well as billions of dollars received in the form of “faith-based” grants. This governmental power is matched by media influence, as the Christian Right also owns several national television and radio networks, as well as many local media outlets. Further, right-wing organizations such as Focus on the Family and the Christian Coalition are controlled by wealthy white male elites who claim to be “close to God” and are followed with feverish obedience by millions of supporters.

The best parts of the book are the interview sections which delve into the lives of the people drawn to, and spit out by, this movement. By humanizing the participants, we come to understand that their immersion into this Christian reality is often a flight from an overwhelming sense of meaninglessness and despair, genuine emotions which develop from real-world sufferings like unemployment and abuse.

However, much of the book does not live up to this potential and consists of Chris Hedges sending forth litanies of blanket indictments against the ideology of the Christian Right, and attaching a somewhat monolithic character to what in reality is probably a more scattered and heterogeneous right-wing Christian population. In other words, by attacking them as potentially all-powerful, do we not in fact imbue them with powers they do not actually possess?

Worse, although the author rightly argues we must not tolerate a movement which does not tolerate us, he leaves us with little useful ammunition for that struggle. Condemnations of fundamentalist thinking and similarities to Nazism will only get us so far, we need to locate the weak points in the armor of these Crusaders, and this book unfortunately serves little in developing such a strategy.

In a present and future marked by severe crises of an economic, ecological and social nature, the seductiveness of movements urging apocalyptic violence unfortunately may become quite great, and only an alternative movement that appeals to the best in humanity can prevent the emergence of a dictatorship of fear. That great Christian principle of love must be the guiding force as we address the mounting grievances of those left behind by this society and point towards a better future.

“Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture”

“Cows, Pigs, Wars, and Witches: The Riddles of Culture”

by Marvin Harris

1974 Random House

Why do Jews and Muslims refuse to eat pork? Why were thousands of witches burned at the stake during late medieval Europe? These and other riddles are explored by famous anthropologist Marvin Harris, and his conclusions are simple: people act within social and ecological contexts that make their actions meaningful. Put another way: cultural ideas and practices that seem strange to us may actually be vital and necessary to the people of those cultures.

Harris is especially good at explaining how societies create elaborate rituals to avoid harming the natural ecosystems they depend on, which clarifies the Middle Eastern ban on pig products. It turns out the chubby animals compete with humans for the same foods. Raising them in large numbers would place great strain on a land made fragile by thousands of years of deforestation and desertification. Better to ban them entirely and not risk further ecological damage.

This logic is then extended to elucidate why the institution of warfare probably first arose as a way to limit population pressure on the environment. In Harris’ words, “In most primitive societies, warfare is an effective means of population control because intense, recurring intergroup combat places a premium upon rearing male rather than female infants.” Since the rate of population growth depends on the number of healthy women, privileging males by making their larger bodies necessary for combat is a way of reducing the need to “eat the forest.” Not that male supremacy and violence is the BEST way to curb population growth, but it’s one ritual that societies have adopted to meet that goal.

This discussion of patriarchy leads to an exploration of class. The emergence of “big men”, chiefs, and finally the State is explained as a cascading distortion of the original principles of reciprocity into the rule of redistribution. “Big men” work harder than anyone in their tribe to provide a large feast for their community – with the only goal being prestige. Chiefs similarly pursue prestige, and plan great feasts to show off their managerial skills, but they themselves harvest little food. Finally “we end up with state-level societies ruled over by hereditary kings who perform no basic industrial or agricultural labor and who keep the most and best of everything for themselves.” At the root of this construction of inequality is the impetus to make people work harder to create larger surpluses so that greater social rewards can be given out to show off the leader’s generosity. But only at the State or Imperial level is this hierarchy enforced not by prestige but by force of arms, to stop the poor and working classes from revolting and sharing the fruits of their labor.

The most provocative sections of the book deal with revolutionary movements that fought for this liberation, within the context of the religious wars of Biblical Judea and Late Medieval Europe.

First, Harris tackles the Messiah complex Read the rest of this entry »

Salt of the Earth is a classic organizing movie about striking Mexican-American miners and their wives. Based on an incredible true story, the 1953 film follows the organizing efforts of the town’s women, who must overcome the company’s classism, the sheriff’s racism, as well as their own husband’s sexism, to win the strike (while the men stay at home and take care of the house and children). Highly recommended!

This is just the first segment of the movie, make sure to click the Up-Arrow button to watch the rest!

“Yes Means Yes! Visions of Female Sexual Power and A World Without Rape”

“Yes Means Yes! Visions of Female Sexual Power and A World Without Rape”

Jaclyn Friedman & Jessica Valenti

2008 Seal Press

Easily the best book I’ve read this year, if not ever. Yes Means Yes! is an anthology of essays from women and trans folks (and a few men) of all backgrounds, white, black, Latina, Asian, poor, affluent, queer, hetero, sex workers, dominatrices, bloggers, organizers, educators, artists, and survivors, all answering the question, “How can we create a world without rape?”

This book more than any other opened my eyes to the central importance of female sexual power to movement for progressive social change. Through dissecting sexual assault and “rape culture” from ALL angles, the writers articulate that the objectification and control of female bodies is literally the cornerstone of patriarchal society. Therefore efforts to reclaim female body sovereignty and sexual power are at the forefront of revolutionary change.

This book does not just offer women tips on how to avoid sexual assault (although it does encourage self-defense classes!), it courageously directs blame at the male-dominated society that puts women in dangerous situations on a daily basis. Similarly, as should be obvious from the title, this work is not just about teaching men to respect “No”, but showing women (all people really) how to love their bodies and embrace their sexuality, in whatever way it manifests. Enthusiastic consent, responding to “Yes!” and cautious “Maybes”, and taking things one step at a time without assumptions or feelings of entitlement to orgasm, while respecting the ability of a sexual partner to say “Stop.” at any moment, shows a way to the best and most liberatory sex imaginable.

But the book covers so much more than consent. This is a feminist handbook for the masses: well-written, varied, practical, theoretical, yet accessible.

It’s hard to pick a favorite essay, but the one that spoke to me the most was “Killing Misogyny: A Personal Story of Love, Violence, and Strategies for Survival” by Cristina Meztli Tzintún, a personal story about overcoming abusive and controlling male partners. Cristina relates how she got involved with a “radical, feminist” man of color and bonded through activism. Before she knew it she was years into an abusive relationship that gave her STDs and an inability to leave him, despite his cheating on her with his students, half his age. The pattern mirrored her parents’ disastrous marriage, which made it even more depressing that she could not break free of the cycle of abuse.

While it’s easy to demonize her partner, Alan, a more honest reading will recognize some of his patterns in each of us who have been male-socialized. For example, entitlement to women’s bodies and lack of consideration for the emotional damage wrought by selfish actions are things I know I have to struggle against. Cristina’s bravery in leaving Alan and demanding accountability for his assaults should encourage all of us, that misogyny can in fact be beaten and that personal transformation is an incredibly political act.

I can’t recommend this collection highly enough. Everyone needs to read this book.

“The Mass Psychology of Fascism”

“The Mass Psychology of Fascism”

by Wilhelm Reich

1946 The Noonday Press

First written in Germany in 1932 as Hitler was coming to power, then revised in the US in 1944, this is a classic study of the characteristics of fascist movement. Reich, a former Marxist from the Frankfurt School, emphasizes that fascism is not unique to Germany or Japan or Italy, but is instead “the basic emotional attitude of the suppressed man of our authoritarian machine civilization and its mechanistic-mystical conception of life.”

In other words it’s not enough to blame Hitler or the Nazis or any political party for the rise of fascism, we have to understand why millions of people have been, and continue to be, drawn to Right-wing movement (its mass character is what distinguishes fascism from simple authoritarianism). Finding its base in the Middle Classes, fascist movement feeds upon authoritarian patriarchal social structures, especially the father-dominated family, which prepares children to obey and even revere a harsh “leader.”

But what was most interesting to me about this book is the politics of sexuality. Reich as a psychiatrist observed that the repression of sexuality, especially from a young age, prepares people for lifetimes of neurotic self-hatred as some of their most basic and healthy life functions become embedded with deep shame and guilt. I would add, sexual assault and child abuse add much fuel to this fire. Reich stresses that children, adolescents and women are perpetually denied control over their sexual desires and bodies, which is what gives the patriarchal father so much power in the family, and therefore the sexual repression of masses of people becomes the seeds that grow fascist political movements.

I will write more on this train of thought in my review of Yes Means Yes!, and it’s also something I’ve been sparked to consider after watching the film The Handmaid’s Tale, about a dark future where pollution has made most women sterile, and a Christian fascist movement seizes control of society to make the remaining fertile women into the sex slaves of powerful male leaders. It’s surprisingly realistic in some scary ways, because it builds from the sad truth that the patriarchal Christian Right is a real force in society and continues to attack the rights of women to control their own bodies and sexuality. This tendency must be overcome, by women and trans folks taking back their body sovereignty and proclaiming their sexuality as no one’s but their own.

Part 1 of The Handmaid’s Tale. Read the rest of this entry »

More and more people are using the language of peak oil and becoming aware that the future we once took for granted is now being foreclosed (not incidentally, by the same folks who are foreclosing a lot of our homes). It is increasingly clear that we stand at a cross-roads, and that neither road leads anywhere similar to the global capitalist era we just passed through.

Here are some excerpts from a good article that acknowledges the reasons why the future will be nothing like the past, and lays out the 2 paths we can now head down. I wrote some thoughts at the end to inspire us to think realistically and demand the impossible. [alex]

Time to Deliver: No Turning Back, Part I.

by Sara Robinson

April 7, 2009

Originally published by Campaign for America’s Future

..[T]he two dominant scenarios about the American future that progressives seem to be wrestling with right now [might be described as]:

1) Permanent Decline — Due to Americans’ native hyperindividualism, political apathy, and overweening willingness to accept personal blame for their country’s failures, the corporatists finally succeed in turning the US into Indonesia. This time, we will not find the will to fight back (or, if we do, it will be too late). As a result, in a few years there will be no more middle class, no upward mobility, few remaining public institutions devoted to the common good, no health care, no education, and no hope of ever restoring American ideals or getting back to some semblance of the America we knew.

2) Reinvented Greatness — Americans get over their deeply individualistic nature, come together, challenge and restrain the global corporatist order, and finally establish the social democracy that the Powers That Be — corporate, military, media, conservative — have denied to us since the 1950s. This happens in synergy with a move to energy and food self-sufficiency, the growth of a sustainable economy, a revival of participatory democracy, and a general renewal of American values that pulses new life into our institutions and assures us a much more stable future.

Conservatives and the mainstream media, of course, are also offering a third scenario:

3) Happy Face — Prop up the banks, keep people in their houses, and by and by everything will get back to “normal” (defined as “how it all was a few years ago.”)

[Sara recognizes that this third “road” is an illusion, for the following underlying realities which cannot be ignored any longer. -alex]

1. Energy regime change

The first reason there’s no going back to the way it was is that there’s simply not enough oil left in the ground — or carbon sinks left in the world — to sustain America as we’ve known it. We may well be able to sustain some semblance of that way of life (or perhaps, find our way to one even more satisfying); but we won’t be running it on oil or coal.

And when the oil goes, so goes the empire. Read the rest of this entry »

Recent Comments