You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Class’ category.

This shocking article in the UK Independent shows the deadly effects of asbestos in England, where just as in my home town of Ambler, people continue to die from an industry that stopped producing decades ago.

Among the revelations here are that UK officials knew about the “evil effects” of asbestos in 1898, yet it took a century to outlaw. Another startling statistic is that asbestos kills 90,000 people a year worldwide, and the death rate in England will continue to increase until 2016.

More evidence of the social and ecological harm inherent in a capitalist system that values profit above all else.

[alex]

Asbestos: A shameful legacy

The authorities knew it was deadly more than 100 years ago, but it was only banned entirely in 1999. The annual death rate will peak at more than 5,000 in 2016 – now MPs have a chance to do the decent thing.

By Emily Dugan

Sunday, 22 November 2009

The story of Barking’s “industrial killing machine” is a story repeated up and down the country where thousands of Britons continue to be blighted by their industrial past. Exposure to asbestos is now the biggest killer in the British workforce, killing about 4,000 people every year – more than who die in traffic accidents. The shocking figures are the grim legacy of the millions of tons of the dust shipped to Britain to make homes, schools, factories and offices fire resistant. It was used in products from household fabrics to hairdryers.

Those most at risk are ordinary workers and their families. Whether it was dockyard workers who unloaded the lethal cargoes, or those in the factories exposed to the fibres, or the carpenters, laggers, plumbers, electricians and shipyard workers who routinely used asbestos for insulation – all suffered. So did the wives who washed the work overalls and the children who hugged their parents or played in the dust-coated streets.

The exposure to asbestos in Britain is largely historical but the death toll is alarmingly etched on our future. Asbestos fibres can lie dormant on victims’ lungs for up to half a century; deaths from asbestos in Britain will continue to rise until 2016.

Nor is it confined to Britain. The World Health Organisation says asbestos currently kills at least 90,000 workers every year. One report estimated the asbestos cancer epidemic could claim anywhere between five and 10 million lives before it is banned worldwide and exposure ceases.

Asbestos was hailed as the “magic mineral” when its tough, flexible but fire-resistant qualities were realised, but for more than a century doctors and others have been warning of its dangers. Asbestos dust was being inhaled into the lungs where it could lie unnoticed before causing crippling illnesses such lung cancer, asbestosis and mesothelioma which one medical professor has described as “perhaps the most terrible cancer known, in which the decline is the most cruel”. Read the rest of this entry »

Also published by The Rag Blog, OpEdNews, Signs of the Times, Interactivist Info Exchange, and Toward Freedom.

Who Were the Witches? – Patriarchal Terror and the Creation of Capitalism

Who Were the Witches? – Patriarchal Terror and the Creation of Capitalism

Alex Knight

November 5, 2009

This Halloween season, there is no book I could recommend more highly than Silvia Federici’s brilliant Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation (Autonomedia 2004), which tells the dark saga of the Witch Hunt that consumed Europe for more than 200 years. In uncovering this forgotten history, Federici exposes the origins of capitalism in the heightened oppression of workers (represented by Shakespeare’s character Caliban), and most strikingly, in the brutal subjugation of women. She also brings to light the enormous and colorful European peasant movements that fought against the injustices of their time, connecting their defeat to the imposition of a new patriarchal order that divided male from female workers. Today, as more and more people question the usefulness of a capitalist system that has thrown the world into crisis, Caliban and the Witch stands out as essential reading for unmasking the shocking violence and inequality that capitalism has relied upon from its very creation.

Who Were the Witches?

Parents putting a pointed hat on their young son or daughter before Trick-or-Treating might never pause to wonder this question, seeing witches as just another cartoonish Halloween icon like Frankenstein’s monster or Dracula. But deep within our ritual lies a hidden history that can tell us important truths about our world, as the legacy of past events continues to affect us 500 years later. In this book, Silvia Federici takes us back in time to show how the mysterious figure of the witch is key to understanding the creation of capitalism, the profit-motivated economic system that now reigns over the entire planet.

During the 15th – 17th centuries the fear of witches was ever-present in Europe and Colonial America, so much so that if a woman was accused of witchcraft she could face the cruellest of torture until confession was given, or even be executed based on suspicion alone. There was often no evidence whatsoever. The author recounts, “for more than two centuries, in several European countries, hundreds of thousands of women were tried, tortured, burned alive or hanged, accused of having sold body and soul to the devil and, by magical means, murdered scores of children, sucked their blood, made potions with their flesh, caused the death of their neighbors, destroyed cattle and crops, raised storms, and performed many other abominations” (169).

In other words, just about anything bad that might or might not have happened was blamed on witches during that time. So where did this tidal wave of hysteria come from that took the lives so many poor women, most of whom had almost certainly never flown on broomsticks or stirred eye-of-newt into large black cauldrons?

Caliban underscores that the persecution of witches was not just some error of ignorant peasants, but in fact the deliberate policy of Church and State, the very ruling class of society. To put this in perspective, today witchcraft would be a far-fetched cause for alarm, but the fear of hidden terrorists who could strike at any moment because they “hate our freedom” is widespread. Not surprising, since politicians and the media have been drilling this frightening message into people’s heads for years, even though terrorism is a much less likely cause of death than, say, lack of health care.1 And just as the panic over terrorism has enabled today’s powers-that-be to attempt to remake the Middle East, this book makes the case that the powers-that-were of Medieval Europe exploited or invented the fear of witches to remake European society towards a social paradigm that met their interests.

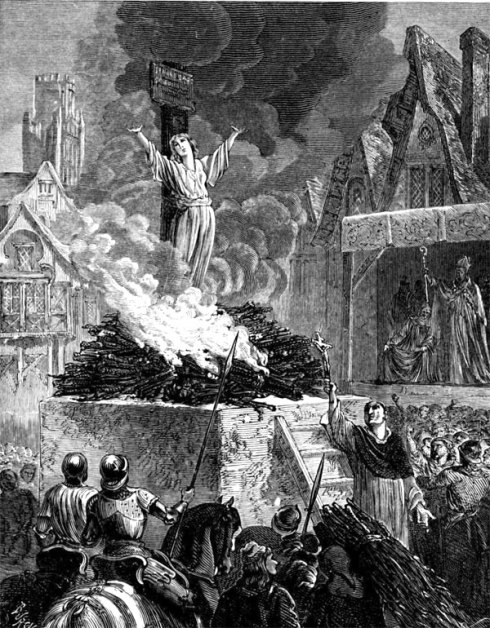

Interestingly, a major component of both of these crusades was the use of so-called “shock and awe” tactics to astound the population with “spectacular displays of force,” which helped to soften up resistance to drastic or unpopular reforms.2 In the case of the Witch Hunt, shock therapy was applied through the witch burnings – spectacles of such stupefying violence that they paralyzed whole villages and regions into accepting fundamental restructuring of medieval society.3 Federici describes a typical witch burning as, “an important public event, which all the members of the community had to attend, including the children of the witches, especially their daughters who, in some cases, would be whipped in front of the stake on which they could see their mother burning alive” (186).

The witch burning was the medieval version of "Shock and Awe"

The book argues that these gruesome executions not only punished “witches” but graphically demonstrated the repercussions for any kind of disobedience to the clergy or nobility. In particular, the witch burnings were meant to terrify women into accepting “a new patriarchal order where women’s bodies, their labor, their sexual and reproductive powers were placed under the control of the state and transformed into economic resources” (170). Read the rest of this entry »

This article only scratches the surface of why capitalism as a system based in constant expansion is absolutely incompatible with a planet of real social and ecological limits, peak oil being one. My book will flesh these arguments out in greater detail, but for now check out what Professor Wolff has been cooking up. [alex]

Peak Oil and Peak Capitalism

by Professor Richard Wolff, March 27, 2009.

Originally posted on The Oil Drum, and on Rick Wolff’s homepage.

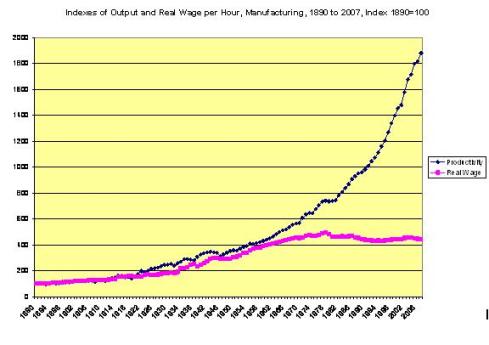

Worker Productivity (blue) vs. Wages (pink), 1890-2009

The concept of peak oil may apply more generally than its friends and foes realize. As we descend into US capitalism’s second major crash in 75 years (with another dozen or so “business cycle downturns” in the interval between crashes), some signs suggest we are at peak capitalism too. Private capitalism (when productive assets are owned by private individuals and groups and when markets rather than state planning dominate the distribution of resources and products) has repeatedly demonstrated a tendency to flare out into overproduction and/or asset inflation bubbles that burst with horrific social consequences. Endless reforms, restructurings, and regulations were all justified in the name not only of extricating us from a crisis but also finally preventing future crises (as Obama repeated this week). They all failed to do that.

The tendency to crisis seems unstoppable, an inherent quality of capitalism. At best, flare outs were caught before they wreaked major havoc, although usually that only postponed and aggravated that havoc. One recent case in point: the stock market crash of early 2000 was limited in its damaging social consequences (recession, etc.) by an historically unprecedented reduction of interest rates and money supply expansion by Alan Greenspan’s Federal Reserve. The resulting real estate bubble temporarily offset the effects of the stock market’s bubble bursting, but when real estate crashed a few years later, what had been deferred hit catastrophically.

Repeated failure to stop its inherent crisis tendency is beginning to tell on the system. The question increasingly insinuates itself even into discourses with a long history of denying its pertinence: has capitalism, qua system, outlived its usefulness? Read the rest of this entry »

The Security Guards at the Art Museum are demanding recognition for their union and an end to poverty wages. Here is their new video presenting their campaign to the incoming CEO of the museum, Timothy Rub:

Welcoming Change at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

The guards are also holding a rally next Sunday to welcome Mr. Rub, check it out! Also see below for more information on the campaign from a recent article in Philadelphia Weekly. [alex]

Welcoming Party for Timothy Rub

2 pm, Sunday, September 6, 2009

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, front “Rocky” steps

•

Join the Philadelphia Security Officers Union and Philly Jobs with Justice as they hold a — “welcoming party” — for incoming museum CEO, Timothy Rub.

•

Security Guards at the museum earn less than $20,000 per year, below the federal poverty line.

•

The Philadelphia Security Officers Union supports the Employee Free Choice Act.

•

We have signed up a majority of the security officers at the Philadelphia Museum on union representation cards.

•

If the Employee Free Choice Act was law right now, we would already be a union.

March with the Philadelphia Security Officers Union in support of card check and the Employee Free Choice Act

2:00 pm—3:30 pm,

come early and take advantage of the free day at the museum

Featuring NYC’s Rude Mechanical Orchestra! It’s a party!

Info: phillyjwj.org

Financial Insecurity

Museum guards ask new director to hear them out.

On April 19, Jennifer Collazo woke up with a $2,882.47 hospital bill. The 33-year-old Army veteran is a Philadelphia Museum of Art security guard employed by the private contractor AlliedBarton. Collazo pays into the medical insurance offered by her employer, but when she came down with severe neck and back pain on the job, she discovered that her health benefits didn’t even cover things like the ambulance ride.

Paltry medical coverage combined with low wages has driven Collazo and other museum guards to organize the Philadelphia Security Officers Union (PSOU). While the museum and AlliedBarton have rebuffed them in the past, guards hope that the institution’s incoming director, Timothy Rub, will be open to dialogue when he takes charge early next month. Read the rest of this entry »

The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy

The Ecology of Freedom: The Emergence and Dissolution of Hierarchy

by Murray Bookchin

1982 Cheshire Books

Murray Bookchin (R.I.P., 2006) was one of the most important American theorists of the 20th century. He is most known for pioneering and promoting social ecology, which holds that “the very notion of the domination of nature by man stems from the very real domination of human by human.” In other words, the only way to resolve the ecological crisis is to create a free and democratic society.

The Ecology of Freedom is one of Bookchin’s classic works, in which he not only outlines social ecology, but exposes hierarchy, “the cultural, traditional and psychological systems of obedience and command”, from its emergence in pre-‘civilized’ patriarchy all the way to capitalism today. The book explains that hierarchy is exclusively a human phenomena, one which has only existed for a relatively short period of time in humanity’s 2 million year history. For that reason, and also because he finds examples of people resisting and overturning hierarchies ever since their emergence, Bookchin believes we can create a world based on social equality, direct democracy and ecological sustainability.

It seems to me this fundamental hope in human possibility is the most essential contribution of this book. In discussing healthier forms of life than we currently inhabit, Bookchin makes a distinction between “organic societies”, which were pre-literate, hunter-gatherer human communities existing before hierarchy took over, and “ecological society”, which he hopes we will create to bring humanity back into balance with nature, but without losing the intellectual and artistic advances of “civilization” (his quote-marks).

Of ‘organic society’ he says “I use the term to denote a spontaneously formed, noncoercive, and egalitarian society – a ‘natural’ society in the very definite sense that it emerges from innate human needs for association, interdependence, and care.” This, he explains, is where we come from. Not a utopia free of problems, but a real society based on the principle of “unity of diversity,” meaning respect for each member of the community, regardless of sex, age, etc. – an arrangement that is free of domination. Read the rest of this entry »

Recent Comments