You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Book Review’ category.

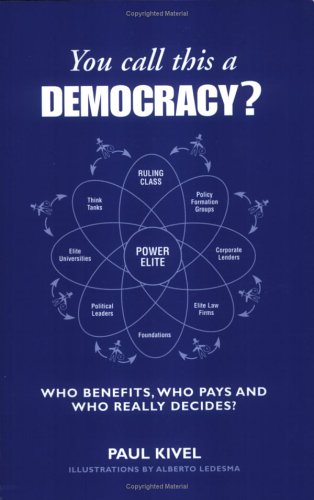

“You Call This a Democracy? Who Benefits, Who Pays, and Who Really Decides?”

by Paul Kivel

2004 Apex Press

Paul Kivel exposes the ruling class of the United States and how it operates in this short, easy-to-read book. With simple concepts and cute illustrations, a nuanced class analysis is presented in a very clear and accessible format.

If the education system was any good at all, “You Call This a Democracy?” would be one of the textbooks used in all high schools. It explains what the ruling class is (those with a family income above $373,000 and net financial wealth of at least $2 million), how it controls the government, media, and economy, and the negative effects we all suffer, such as poverty, wars, disease, pollution, over-working, stress, and meaningless, isolated lives. Kivel particularly does a great job exposing how the ruling class uses racism, sexism, homophobia and other social divisions to keep itself, a relatively small group of basically white Protestant men, in power. Making the connections between systems of oppression is one of the keys to the freedom of everybody, and this book helps move that analysis forward.

There a couple criticisms I could make about the book, first that it doesn’t inspire enough hope or provide much of a systematic solution to the problem that it systematically critiques. And secondly that the book can be cumbersome to read because of a fair amount of repetition coupled with too many general statements about segments of the population. To a certain extent, this was unavoidable in a book of this nature, but I could have used more examples of particular corporations, politicians, and businesspeople and their ilk, even though the examples given in the book are all great.

Definitely check this out if you want to have any idea about the country you’re living in, and how you and your family and everyone you care about are being screwed over by the super-wealthy elite. The path to a democratic future starts when we become informed.

“The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love”

“The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love”

by bell hooks

2004 Washington Square Press

bell hooks defines this project as an attempt to love men enough to understand how patriarchy affects them, and understand how their pain can help them transform and challenge patriarchy. For me it was a profound experience reading this because it touched on so many aspects of my life as a male, from childhood, to school, to sex and relationships, to friendships, etc. It allowed me to see old memories in new ways, and understand that my feelings of pain, confusion and shame were a result of the violent circumstances that I was subjected to growing up in this culture.

In the past I had “understood” patriarchy as something that primarily only affected women, and saw my job mostly as limiting the damage done to the women in my life and organizing. bell hooks pushed me to look inside myself first and foremost and see how this system has terrorized me personally, and how challenging patriarchy is necessary for my own liberation, as well as the liberation of all men, and everybody.

What struck me most significantly was the idea that patriarchy is all the time enforced by violence, and that men are taught through violence to reject their emotions and become cold-blooded and distant, which allows them to commit violence on others.

“Violence is boyhood socialization. The way we ‘turn boys into men’ is through injury… We take them away from their feelings, from sensitivity to others. The very phrase ‘be a man’ means suck it up and keep going. Disconnection is not fallout from traditional masculinity. Disconnection is masculinity.”

I could think of hundreds or thousands of times that I’ve felt this threat of violence keeping me within the shallow emotionless world of patriarchal masculinity. Most often it looks like jokes, put-downs, humiliation, scorn, and exclusion, but violence is at the heart of the matter. In fact, middle school and high school in retrospect look like a 7 year-long gauntlet of violent social training.

Learning to express the pain I’ve felt without shame, and wield my anger not against myself (or others) but against patriarchal society, isn’t something that can change overnight. But bell hooks’ wisdom has opened up new possibilities for me and for all men, and it’s up to us to take the initiative, educate ourselves, get in touch with our own emotions, our own human-ness and connection to others in a non-dominating way, and work together in love and resistance. We don’t just owe it to women, trans and genderqueer folks, we owe it to ourselves.

“Communities of resistance should be places where people can return to themselves more easily, where the conditions are such that they can heal themselves and recover their wholeness.” – Thich Nhat Hanh, The Raft is Not the Shore

“The Tyranny of Oil: The World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do to Stop it”

“The Tyranny of Oil: The World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do to Stop it”

by Antonia Juhasz

2008 HarperCollins

Ever wondered why the US government spends trillions of dollars to launch massive wars against Middle Eastern nations that have never attacked us, but refuses to do absolutely anything about the ongoing climate crisis? This book is for you.

The Tyranny of Oil is an exposee of “Big Oil”, meaning Exxon-Mobil, Chevron, BP, ConocoPhillips, and Royal Dutch Shell, the largest oil corporations in the world (and some of THE largest corporations in the world). The book exposes how these enormous oil octopi have gained virtually total control over the US government, and use their money and political power to make big profits at the expense of the public and the planet. (For example, Exxon Mobil in 2003 posted the largest profits of any corporation in history, then proceeded to beat that record each of the next 5 years).

It all starts with the origin of Big Oil, the mother, Standard Oil. Juhasz stresses the importance of monopolies and corporate mergers, in a sense missing the deeper analysis of capitalism, but nevertheless we come to understand how enormous companies wielding enormous profits can and do undermine democracy.

The book progresses to tell a story about Big Oil’s development and control over the government agencies that are supposed to be regulating it, and finally Big Oil’s plans for the future (War and Trashing the Planet, basically), before an inspirational chapter on What We Can Do. (There’s also a shoutout to SDS here and to our No War No Warming action in DC last year! Cool!)

This is essential reading for all US citizens, because if you aren’t familiar with the concepts she lays out, you frankly have no understanding of the country you live in. Environmental racism, corporate lobbyists and corrupt government agencies, the criminal behavior of Cheney’s Energy Task Force, deregulation and Enron-style fraud, tar sands, and the list goes on.

My only major complaint of the book was the virtual silence on the looming and imminent reality of Peak Oil and how this will transform everything. Juhasz does recognize the scarcity of oil and the likelihood of oil peaking, but chooses to essentially overlook its importance, instead blaming oil companies and speculators for driving up the cost of oil.

This is not just a minor quibble, because the BIG TRUTH is that we’re not just in a struggle against Big Oil, we’re in a struggle against capitalism, and it’s a fight that is reaching perhaps its final act. Peak Oil will challenge the dominant for-profit institutions of power, and can create an opening for social justice activists and organizers to push for much more radical change than appears possible within the current system. Nevertheless, this is probably a subject for another book (mine!), and Juhasz treads on steady ground by appealing to a more mainstream audience and demonizing the oil companies exclusively. This is a very effective book, highly recommended!

Finally, my favorite quote (pg. 325):

“As Paul Wolfowitz said in 1991, ‘The combination of the enormous resources of the Persian Gulf, the power that those resources represent – it’s power. It’s not just that we need gas for our cars, it’s that anyone who controls those resources has enormous capability to build up military forces.'”

“Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights (1919-1950)”

“Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights (1919-1950)”

by Glenda Gilmore

2008 W.W. Norton

I picked up this book randomly when I saw it in the library, and it turned out to be a worthwhile read. Gilmore, a white female professor from North Carolina, surveys the “radical roots of civil rights” through the efforts of the Communist Party in the South during the 1920s through 1940s.

Gilmore tells the story by focusing on a few individual black radicals who have been forgotten by history, especially Lovett Fort-Whiteman and Pauli Murray.

Whiteman, an extravagant early supporter of the Soviet Union, founded some of the first communist organizations for African Americans, before being scared out of the country by the feds, becoming a darling in the Soviet Union, then ultimately winding up in one of Stalin’s gulags in Siberia, where he worked/starved to death.

Murray had more luck, despite being a transgendered black woman in the South in the 1940s. With a bold attitude, she attempted to integrate various institutions, like the University of North Carolina Law program, and although she herself was not successful in these efforts, her example paved the way for future victories within the Black Freedom Movement.

We also learn quite a bit about Langston Hughes, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, Max Yergan, and many other heroic characters who fought early and often for equality in the apartheid South.

More interesting to me though was what I learned about movement strategy, for example we explore how the first integrated unions in the South scared the bejesus out of the capitalists, or what it meant for the Communist Party to bring the country’s attention to the case of the Scottsboro “Boys”, or how the “Popular Front” strategy of allying with liberals succeeded, and failed.

The writing is interesting, but could be more purposeful. Defying Dixie focuses probably too much on the Communists, and not on other radicals, but still this book really clarified for me important stuff like the Depression, the South in the 1930s, and the early Civil Rights Movement, and how once-radical ideas like social equality of the races is now accepted fact (even though still not fully realized).

“Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia”

by Matthew J. Countryman

2007 University of Pennsylvania

This book was not quite what I expected, but I’m not sure what I was expecting. The strength of Up South is that it gives a broad overview of the 1940s-60s civil rights/black power movement in Philadelphia, which was very helpful for me as someone who wanted to learn more about the history of the city I’m living in, especially about the work against racism in one of the most racially divided cities in America.

The book captures a really interesting narrative from postwar liberalism to early-60s protest, to late-60s radicalism, to 70s electoral politics. Along the way we meet some of the most important players, like Cecil B. Moore, Philadelphia Welfare Rights Organization, and Council of Organizations Philadelphia Police Accountability and Responsibility (COPPAR). We learn a bit about their strategies, we learn about the white backlash and Frank Rizzo, and attempts by the system to co-opt and dilute the movement through politics and money.

However, the book also lacks in some substantial ways. For one thing, the author is a professor in Michigan, who as far as I know is not from Philadelphia and is not black. This doesn’t mean he has nothing valuable to contribute from his research, but it does mean the writing is overly academic and emotionally detached.

My other major complaint is that while the book doesn’t heat up until about pg. 120 with chapter 4, the conclusion is way too short and very unsatisfying. It’s only 1 page, front and back, and only hints at the issues which are crying out to be examined.

For example, did the huge protests and deep radicalism of the late 60s really get co-opted into pointless electoral campaigns? How is that possible, and why did it happen?

Why wasn’t there sustained grassroots pressure to hold the newly-elected black politicans accountable, or if there was, why did it fail?

How did the Rizzo Mayorship of the 70s affect the black freedom movement in Philly? In what ways did Rizzo gain greater power in moving from his position as Police Commissioner, and in what ways was he held more accountable as Mayor? More generally, how much did it matter who was in charge of the city government, as far as the movements were concerned?

These are just a few questions that I wish had been addressed in the book more substantially, but I think the fact that the book left me wanting to know more actually points to the success of the book in captivating my interest.

This wasn’t the holistic and movement-centered study that I was looking for, but it helped me clarify my questions on the subject so I recommend it for anyone living in Philadelphia and wanting to know more about the history of their city.

“No Surrender: Writings from an Anti-Imperialist Political Prisoner”

“No Surrender: Writings from an Anti-Imperialist Political Prisoner”

by David Gilbert

2004 Abraham Guillen Press/Arm the Spirit

I recommend this book. David Gilbert, lifelong political prisoner in New York since 1981, and former member of the Weather Underground (now being exploited in McCain political ads), here writes on many subjects of interest to all anti-imperialist activists.

David’s a great writer; very straightforward, focused, but with tenderness and humor, and he has a way of making sense of complicated and terrible political dramas in short and effective little essays. In addition to essays on Gilbert’s own history in SDS and Weather, the best samples here are on the U.S. white working class historically, the prison system, Colombia, Afghanistan, and neoliberalism. But Gilbert delves into a wide array of subjects from feminism to AIDS to institutional racism in many forms, and always with an amazing insight without requiring a lot of effort on the part of the reader.

It’s a damn shame that this man is behind bars, but luckily he’s still able to share his wisdom with us. Check this out!

“I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle”

“I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle”

by Charles Payne

1991 by University of California Press

I’ve Got the Light of Freedom is a book about organizing, for organizers. It chronicles SNCC and the Mississippi Freedom movement from its beginnings to ends, especially highlighting the individual organizers and families that put the movement together and sustained it.

The book is great because it analyzes the movement from a variety of perspectives, including understanding the strategies, tactics, gender dynamics, class dynamics, white/black organizing dynamics, local/rural dynamics, mentorship and leadership development, state and white repression, and the rise and fall of trust and community that were the backbone of the movement. The thread throughout is the brilliance of the Ella Baker/Septima Clark school of organizing, based on meeting people where they’re at and developing their leadership so they can lead their own fights. It’s about valuing the day-to-day work that sustains organizations above the flashy actions or speeches, and about seeing our work as part of a long-term struggle towards freedom that will need to involve millions of people.

My criticisms Read the rest of this entry »

Recent Comments